Community Service

Mathematics is supposed to be a process of discovery. Definitions, propositions, and methods of proof don’t come from nowhere, although after the fact (when presented in a textbook) they often seem to. As opposed to a textbook, real maths is highly non-linear. It took mathematicians quite a lot of fuss to come up with the quadratic formula, and even simple geometric conjectures were for the longest time the subject of hot debate.

I feel like if I’m going to be a teacher worth anyone’s time, I have to let students in on the secret that questions guide mathematics. This urge to teach is especially strong at the high school level, where it is generally agreed that “mathematics education” is a farce.

And so, as the only community service I do regularly (and too seldom, at that), I go to local high schools and middle schools and give “lectures” on mathematics. Though I have ideas for a lot of lectures I could give, and wish I had more than just an hour to work with a class, I usually stick to a particularly intuitive lecture on graph theory. I will reproduce one such lecture here, picking out the best of the student’s innovation that I can remember. Regular text paraphrases what I speak and what is written on the board, quoted text is student response, and square brackets [ ] contain commentary.

As a note to the reader, this will serve as a very detailed introduction to Graph Theory, as opposed to the terse primers I’ve been providing thus far.

Two Puzzles

Today we are going to do three things:

- Think about some puzzles,

- Do some mathematics, and

- Use math to change the world.

So here are the two puzzles:

First, [after asking a student to provide her name, I invent a city name based on it] imagine you’re the mayor of Erintown. In Erintown there are seven very old and beautiful bridges, and as mayor you’d like to promote their prominence in tourism. To do this, you wish to provide a route through the city which crosses every bridge exactly once, never visiting the same bridge twice. The seven bridges are arranged as follows [a much more detailed picture than what one draws on a white board]:

Bridges of Erintown

[The informed reader will recognize this immediately as the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem, which historically founded graph theory, and was solved by Leonard Euler in the 18th century. But honestly, what (potentially immature) high school student is interested in a problem with a name like that? As we will see throughout the post, personalization (and the engagement inherent in it) is essential to the success of the lecture.]

Unfortunately, after a few tries you are unable to find a route which works. Hence the first puzzle is: does such a route exist? If not, how can we prove it?

[At this point, we clarify some rules of the puzzle. High school students are adept at producing loopholes, and rightfully they enjoy doing so. So typically we talk about swimming, aircraft, traversing bridges halfway, teleportation, etc., banishing each possibility as it comes up. This is an important step, because in part the whole point of the mathematical formulation of this problem is to eliminate these possibilities from consideration. We very much need to rephrase this problem entirely in our minds to extract the aspects we care about and discard the rest. Even when in real life swimming is an option, our mathematical formulation must ignore swimming, and hence we must design it appropriately (and hopefully elegantly).]

For the second problem, say you’re at a party of one hundred people. At this party, someone decides to start tallying up who at the party is friends with whomelse (he’s one of those guys, a drama king). He shows his list to you, and you notice that there are two people at the party who have the same number of friends at the party. The thought occurs to you that this will always be the case, no matter how many people attend and who is friends with whom.

So the second puzzle is: at a party of $ n$ people, must it be true that there exist two people with the same number of friends at the party?

[Again, we have the requisite loopholes, like whether there are stalkers at the party, and whether you are friends with yourself. The former drives us to distinguish that we want “symmetric” friendships, i.e. if you are friends with someone then they are friends with you. The former translates to undirected edges later, while the latter hints at simple graphs. Both are usually made clear by appealing to the rules of Facebook friendship. Finally, we might make the clarification that there are at least two people at the party, in order to prevent a discussion of vacuously true statements.]

Now take five minutes and try to solve these problems, by yourself, with a friend, or with a group, however you feel most comfortable tackling a problem. [They never get very far, but at least once I’ve encountered a student who knew of the Seven Bridges problem ahead of time, spoiling much of the fun and thoroughly confusing the rest of the class.]

New Mathematics

[After five to ten minutes pass and the group is quiet again] So, who thinks they’ve solved the first problem? [hands raise, most proclaiming impossibility; those who try to explain their reasoning mostly resign to awkward case-checking or saying they just couldn’t find one that worked] And what about the second? [nobody raises a hand, most enjoy thinking about the bridges problem because it is very visual. In classrooms blessed with a SmartBoard, I can have a number of them come up to the front and attempt to draw a route with their finger (and hitting undo when they invariably fail, so that I don’t have to redraw the diagram every time).]

So, it appears that we haven’t come up with a good solution for either problem. Now a mathematician might say at this point, “screw this, I’m going to make up my own math to solve it!” And that’s what we’re going to try to do.

The first step is to compare the problems: what is similar and what is different? [Discussion ensues, but often times the students don’t understand what I’m looking for, and usually the problem is that they’re trying to come up with the “correct” answer instead of making observations; it is a curse of the schooling paradigm. Additional leading questions include:] what are the subjects of our study? How are they related? does it matter where you walk on a landmass between visiting bridges? Does it matter where the people in the party are standing? [And the most important question] Is there a better way to draw these problems?

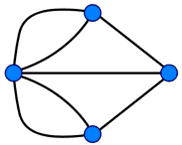

[Soon enough students make the right observations, that our drawings of the two problems are almost identical!] It doesn’t actually matter how big or where the landmasses are, since all we care about is the order in which we cross bridges. Hence we can compress the landmasses down to dots! Additionally, we can just draw people as dots, and arrange them in any way we wish. Then, the bridges and friendships become lines connecting the dots. This yields a much nicer picture for the bridges problem, and a similar one for the party problem.

By writing the problem this way, we have distilled out the relevant facts: all we really care about is the structure of how these things are connected**.** Unfortunately we have one problem: we don’t have names for these things! We certainly don’t want to call them bridges and landmasses, or people and friendships, because we want the picture to apply to both problems at the same time.

So to start, what would we call the picture as a whole? Appeal to your imagination about what it looks like. [Though this part is sometimes difficult, especially at the middle-school level, eventually someone calls out something truly clever] “How about a constellation?”

I like that! So here we are, this is our invention:

Constellation Theory

What are we going to call the individual dots? “Stars!” And what about the lines connecting them? “How about…connections?” Okay. So here is our first definition:

Definition: A constellation has three parts:

- A set of stars $ S$ [we just accept the intuitive definition of a set without issue],

- A set of connections $ C$,

- A function $ f: C \to S \times S$ which accepts a connection and tells us which two stars it is connected to.

[Before the third, I ask the class whether the first two alone are enough. If I get nods, I draw a random collection of dots and lines, with the lines not at all connected to the dots, and they see we need some statement of incidence.]

Don’t be afraid of the third part (even if you don’t know what a function is), it’s just a formality that uses other (well-established) maths to make our definition consistent. Math can sometimes be a notational nightmare, but all this means is that we can take any connection and easily say which two stars it connects. Since we will always draw constellations as a picture, we can just use the picture as our “function.”

Now can someone remind me again what we were looking for in the bridges problem? Right, a route through the city that hits every bridge exactly once. First we need to translate a “route” into our language of constellations. Does anyone have a good name? [After a few generic suggestions like “trail,” “path,” and “route,” we settle on the imaginative “waltz”.] This gives our second definition:

Definition: A waltz through a constellation $ (S,C,f)$ is a list of alternating stars and connections, which we label $ (s_1, c_1, s_2, c_2, \dots, s_{n-1}, c_{n-1}, s_n)$, where the $ i$th connection $ c_i$ is connected to its neighboring stars in the list $ s_i, s_{i+1}$. In terms of our function, $ f(c_i) = (s_i,s_{i+1})$ for each $ i=1 \dots n-1$.

This is just a way to write out on paper what the waltz is. [I label the seven bridges picture and provide an example.] You who suggested the name “waltz,” what is your name? “Phil.” What is your last name, Phil? “Osman.” Great! Now we have another definition:

Definition: An Osmannian waltz through a constellation is a waltz which uses each connection in $ C$ exactly once.

[A few giggles resound when they realize I’m incorporating the student’s name into the definition.] Now can somebody rephrase the original problem in terms of constellation theory? “We want to find out if there is an Osmannian waltz in that particular constellation.” Excellent!

Now let’s turn our attention to the party problem. Can someone remind me what we were trying to find out about parties? “Whether there are two people who have the same number of friends.” Right, whether that has to be the case for any party. Now in terms of constellations, what is that? “The number of connections at each star.” Great. What’s your name? “Olivia.” Olivia, what’s your last name? “Bisel.” Okay. Here’s another definition:

Definition: The Bisel-degree of a star is the number of connections in $ C$ connected to it.

Now there are a couple of other details we have to consider. Specifically, in a general constellation we never ruled out multiple connections connecting the same two stars. And we never said a connection can’t go from a star to itself. But we must rule these out to make a sensible party problem. So we will call a constellation which rules out doubled connections and self-connections simple. [For the sake of time, we just provide a name, and it’s not that imaginative of a property anyway.]

So can someone translate the party problem into the language of simple constellations? “It’s whether every simple constellation has to have two stars with equal Bisel-degree.” Wonderful!

Now that we have a working language, let’s take another ten minutes to try to solve the problems. But this time, you aren’t allowed to use “bridges,” “landmasses,” “people,” or “friendships” anymore, you have to use the terms we invented. [The students still don’t get far, especially on the bridges problem, but every now and then a student solves the party problem. As they work, I give subtle hints, like, “what happens if you add extra connections or remove some? Does it work then? What aspect of the intrinsic structure have you altered by doing this? Try lots of examples!”]

[After bringing the class back together] So who thinks they’ve solved the first problem? [a few hands raise] “I think it has something to do with whether the Bisel-degree is even or odd.” Interesting. Did you get much further than that? “No…” Okay. What about the party problem? “I think I have it. So if everybody had a different number of friends, then one person would have to have no friends and someone would have to be everyone’s friend, but that can’t happen.”

Did everyone hear that? [I reiterate on the board in detail, explaining the idea behind proof by contradiction, and drawing a picture of the resulting constellation.] This is a very elegant proof. And if anyone can come up with a solid proof of the bridge problem, I have no doubt your teacher would give ample extra credit.

Changing the World

Now, for the mathematician this is enough. This new mathematical object, a constellation, is full of wonderful patterns that we could spend our entire lives thinking about (and many have done just this). However, it’s probably true that most of you aren’t going to become mathematicians. So let’s try to think of things in the real world that we can model as constellations. Any ideas?

[The students suggest a variety of different (and usually complex) ideas, including trade between nation-states, distributions of power among people, and the structure of galaxies. For each example, I usually have to verbally augment our representation of a graph (for the sake of time), bringing constellations with numerically labeled edges or directed connections. Since I always tell the students to “think bigger,” they inevitably say “galaxies,” and I have to explain why that doesn’t work, because the whole point of constellations (the mathematical ones) is that the relative sizes and positions of the stars don’t matter, whereas at the galactic level that completely determines the connection (which is invariably gravitational pull). We apologize for the terminological confusion.

[Eventually, we might get to the cases of modelling all roads and intersections, after which I claim that is exactly how Google Maps (and all other mapping/directions software) works. Sometimes they take the “friendship” hint and recognize Facebook as a constellation, and we often begin to talk about friend suggestions and degrees of separation. Finally, (and this is the main example I wish to work toward), we model the entire internet as a constellation, with directed connections corresponding to links between web sites. Then I talk about how Google based their company on the soundness of this particular model, making 25 billion dollars and changing the world. We do not discuss software representations of constellations, nor algorithms to extract data from them (this would be a whole course worth of information, at least).

[Depending on the amount of remaining time, I either provide the proof of the party problem, if the students didn’t solve it on their own, or continue with anecdotes about Google’s PageRank and its pitfalls. I don’t usually give the proof of the seven bridges problem, but if pressed a short sketch of the proof is easy. More often than not, the bell ends my lecture before I’m ready anyway.]

[I should emphasize that the proof of the party problem is the most exciting moment of the entire lecture. There is often a few students that have an audible “whoa!” and I’ve even received a standing ovation. This tells me that basic elegant proofs are easily within reach of a freshman high school student, and even the obviously “popular” girls have admitted to me it’s cool.]

Reflections

This lecture has generally been successful among students for three obvious reasons.

First, it is exploratory. People intrinsically like puzzles. In sharp contrast to the typical high-school style of memorization and repetition, the students drive the method! Of course, they do so in a discordant, chaotic way, but this can just as easily be said of the same students English essays or history papers. They simply have less practice with this particular kind of argument, and so they are expectantly less coherent.

Unfortunately the shortage of time forces me to guide them much more directly than I should. The amount of content we cover in an hour lecture really deserves a week of discussion, formulation and reformulation, and debate, with as little intervention as possible. I would absolutely love a chance to work with them for an extended period of time to see how it plays out. And of course, it would be much less linear, and we’d explore the questions of the students interest. However, I do fear that they might prefer a more rigid structure, being used to the humdrum of their education heretofore.

Second, the lecture is personal. I don’t have them make up names for nothing. Mathematics is a generative subject. The students not only need to see that, but also experience the process of taking an intuitive idea and nailing it down (often with more logical rigor than anything they’ve experienced in math to date). Inventing a name for the resulting definition secures the idea in their memory, and accentuates the notion that this thing is unique to their special classroom community. Since they don’t yet have the practice or motivation to make their own proofs (the ultimate mathematical self-expression), this is the next best thing. But most of all, naming the concepts is fun!

So I frame the problems in their imaginations, not history. I give them no false pretense for why we are doing this. The puzzle is a means to its own end, and we only later discover that our work is applicable. For a large portion of mathematical history, one might argue, this is how progress worked. Certainly Leonhard Euler anticipated neither Facebook’s social graph nor Google Maps in the mid 18th century. This is the easiest way to impress upon them that many different things have similar patterns in their structure, so even studying a trivial thing can be very enlightening. The puzzles really are worth doing for their own sake.

Compare this to being given the definitions and propositions in the established mathematical language. To an untrained, uninterested student, this is not only confusing, but boring beyond belief! They don’t have the prerequisite intuition for why the definition is needed, and so they are left mindlessly following along at best, and dozing off at worst.

Third, the lecture is a conversation. While ultimately I have to dish out judgement on their suggestions (this name doesn’t make sense, that idea doesn’t pan out for this reason, etc.), I make an honest effort to explain why and reiterate our goals, showing the discrepancy, and then requesting another suggestion. Unfortunately that keeps it as a bona-fide lecture, but if I had a week, the students would ideally critique each other’s work.

At the same time, I do (to some bounded level) entertain their admittedly immature suggestions. When they keep insisting swimming or long jumping across the river, I usually quip with something like, “Pretend the tourist is your grandmother. Would she swim that far?” If not to just deny their question, this reminds them that the original puzzle was meant for all tourists, including the “weakest link” as far as swimming goes. Even when they riposte with “Yes. My grandmother is a body-builder,” I dismiss it with a smirk and a wave of the hand, perhaps sarcastically saying, “Okay.” I feel that such a level of humorous improvisation is necessary, both to keep the students on their toes and to mirror their creativity with my own, thus fueling it and directing it toward the mathematics.

Of course, I might not always spend so much time with such verbal fencing. But for a first exposure to real mathematics, and to establish my role in part as an equal but more so as an obstacle, I deem it necessary. I need to be the out-witter, so that when they exhaust their loopholes, they have no choice but to beat me by solving the problem. Given a lengthier period of time (taking into consideration the students’ maturity level), I would gradually transition to a more pointed focus on the problems, and make it clear when silliness is appropriate. With luck and planning, interest in the problems would compensate for a perhaps dull state of order.

If I Had a Class

Sometimes I entertain the thought that I might end up teaching high school, and that with the providence of the school’s administration I could have my own elective course called “Real Math,” or something perhaps more enticing to the skeptical student (“Math Soup for the Teenage Soul”? “Math as Art”? “Mathematical Composition”?).

This course would start with a week of lectures similar to the one detailed above, and then alternate each week between some objective curricula (likely the basics of set theory and methods of proof) and an exploratory topic. The latter might likely start off as more explorations into graph theory (I’d debate whether to replace their invented names with the established language) and then continue into other basic topics. During the exploratory week, students would present and critique arguments in front of the class. The problems come from a list of problems given at the beginning of the week or the students’ own minds. And though I’d prefer most of the problems being the students’ own, it’s likely that initially most of the problems would come from me. Partial solutions, interesting observations, and even the process of an incorrect solution would all be presentation-worthy.

And finally, perhaps the only original idea I would have for this course, the students would each keep a journal. It would double as a notebook for their own investigation of the material brought up during exploratory weeks and a portfolio to turn in for grading. Its grading would be largely subjective, but the students would have to display some level of effort in terms of the depth to which they explore a particular problem and the number of problems attempted. As the year would progress, I would get to know the students’ ability levels and work tendencies much more clearly, and would thus have a more refined and personalized grading method.

Of course, not long after building up these ideas in my imagination, I came across the essay A Mathematician’s Lament, in which Paul Lockhart mercilessly (and rightfully) berates the current state of mathematics education in America. He more or less advocates the kind of teaching style I propose, and then argues that today’s mathematics teachers cannot play such a role for a lack of their own love for mathematics, and would not want to, because teaching this way is extremely hard! It requires much more work than the average teacher is paid to do, and there is no time for it when you’re berated by scripted curricula and standards and have six classes a day.

After repeating the lecture above for five classes of students in the course of a single day, I certainly agree with Lockhart on the difficulty of this teaching method. Though I feel I have a natural knack for presentation and engagement, to handle the standard number of students per day expected of American teachers is quite tiring (and I am a lively and strapping young lad!). It’s clear that if mathematics education is going to be fixed, one big part will be in taking teachers out of the classroom for preparation, training, and reflection. That being said, I consider it my duty to take every opportunity to do a lecture, while it provides me both with intellectual joy and the satisfaction of beneficence.

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.