In this post we’ll cover the second of the “basic four” methods of proof: the contrapositive implication. We will build off our material from last time and start by defining functions on sets.

Functions as Sets

So far we have become comfortable with the definition of a set, but the most common way to use sets is to construct functions between them. As programmers we readily understand the nature of a function, but how can we define one mathematically? It turns out we can do it in terms of sets, but let us recall the desired properties of a function:

- Every input must have an output.

- Every input can only correspond to one output (the functions must be deterministic).

One might try at first to define a function in terms of subsets of size two. That is, if $ A, B$ are sets then a function $ f: A \to B$ would be completely specified by

$$\displaystyle \left \{ \left \{ x, y \right \} : x \in A, y \in B \right \}$$where to enforce those two bullets, we must impose the condition that every $ x \in A$ occurs in one and only one of those subsets. Notationally, we would say that $ y = f(x)$ means $ \left \{ x, y \right \}$ is a member of the function. Unfortunately, this definition fails miserably when $ A = B$, because we have no way to distinguish the input from the output.

To compensate for this, we introduce a new type of object called a tuple. A tuple is just an ordered list of elements, which we write using round brackets, e.g. $ (a,b,c,d,e)$.

As a quick aside, one can define ordered tuples in terms of sets. We will leave the reader to puzzle why this works, and generalize the example provided:

$$\displaystyle (a,b) = \left \{ a, \left \{ a, b \right \} \right \}$$And so a function $ f: A \to B$ is defined to be a list of ordered pairs where the first thing in the pair is an input and the second is an output:

$$\displaystyle f = \left \{ (x, y) : x \in A, y \in B \right \}$$Subject to the same conditions, that each $ x$ value from $ A$ must occur in one and only one pair. And again by way of notation we say $ y = f(x)$ if the pair $ (x,y)$ is a member of $ f$ as a set. Note that the concept of a function having “input and output” is just an interpretation. A function can be viewed independent of any computational ideas as just a set of pairs. Often enough we might not even know how to compute a function (or it might be provably uncomputable!), but we can still work with it abstractly.

It is also common to call functions “maps,” and to define “map” to mean a special kind of function (that is, with extra conditions) depending on the mathematical field one is working in. Even in other places on this blog, “map” might stand for a continuous function, or a homomorphism. Don’t worry if you don’t know these terms off hand; they are just special cases of functions as we’ve defined them here. For the purposes of this series on methods of proof, “function” and “map” and “mapping” mean the same thing: regular old functions on sets.

Injections

One of the most important and natural properties of a function is that of injectivity.

Definition: A function $ f: A \to B$ is an injection if whenever $ a \neq a’$ are distinct members of $ A$, then $ f(a) \neq f(a’)$. The adjectival version of the word injection is injective.

As a quick side note, it is often the convention for mathematicians to use a capital letter to denote a set, and a lower-case letter to denote a generic element of that set. Moreover, the apostrophe on the $ a’$ is called a prime (so $ a’$ is spoken, “a prime”), and it’s meant to denote a variation on the non-prime’d variable $ a$ in some way. In this case, the variation is that $ a’ \neq a$.

So even if we had not explicitly mentioned where the $ a, a’$ objects came from, the knowledgeable mathematician (which the reader is obviously becoming) would be reasonably certain that they come from $ A$. Similarly, if I were to lackadaisically present $ b$ out of nowhere, the reader would infer it must come from $ B$.

One simple and commonly used example of an injection is the so-called inclusion function. If $ A \subset B$ are sets, then there is a canonical function representing this subset relationship, namely the function $ i: A \to B$ defined by $ i(a) = a$. It should be clear that non-equal things get mapped to non-equal things, because the function doesn’t actually do anything except change perspective on where the elements are sitting: two nonequal things sitting in $ A$ are still nonequal in $ B$.

Another example is that of multiplication by two as a map on natural numbers. More rigorously, define $ f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}$ by $ f(x) = 2x$. It is clear that whenever $ x \neq y$ as natural numbers then $ 2x \neq 2y$. For one, $ x, y$ must have differing prime factorizations, and so must $ 2x, 2y$ because we added the same prime factor of 2 to both numbers. Did you catch the quick proof by direct implication there? It was sneaky, but present.

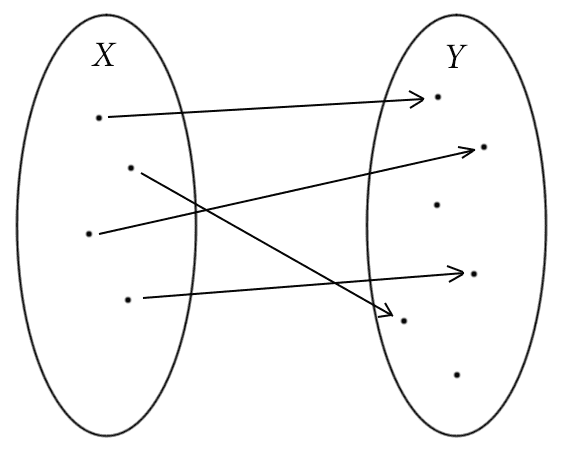

Now the property of being an injection can be summed up by a very nice picture:

A picture example of an injective function.

The arrows above represent the pairs $ (x,f(x))$, and the fact that no two arrows end in the same place makes this function an injection. Indeed, drawing pictures like this can give us clues about the true nature of a proposed fact. If the fact is false, it’s usually easy to draw a picture like this showing so. If it’s true, then the pictures will support it and hopefully make the proof obvious. We will see this in action in a bit (and perhaps we should expand upon it later with a post titled, “Methods of Proof — Proof by Picture”).

There is another, more subtle concept associated with injectivity, and this is where its name comes from. The word “inject” gives one the mental picture that we’re literally placing one set $ A$ inside another set $ B$ without changing the nature of $ A$. We are simply realizing it as being inside of $ B$, perhaps with different names for its elements. This interpretation becomes much clearer when one investigates sets with additional structure, such as groups, rings, or topological spaces. Here the word “injective mapping” much more literally means placing one thing inside another without changing the former’s structure in any way except for relabeling.

In any case, mathematicians have the bad (but time-saving) habit of implicitly identifying a set with its image under an injective mapping. That is, if $ f :A \to B$ is an injective function, then one can view $ A$ as the same thing as $ f(A) \subset B$. That is, they have the same elements except that $ f$ renames the elements of $ A$ as elements of $ B$. The abuse comes in when they start saying $ A \subset B$ even when this is not strictly the case.

Here is an example of this abuse that many programmers commit without perhaps noticing it. Suppose $ X$ is the set of all colors that can be displayed on a computer (as an abstract set; the elements are “this particular green,” “that particular pinkish mauve”). Now let $ Y$ be the set of all finite hexadecimal numbers. Then there is an obvious injective map from $ X \to Y$ sending each color to its 6-digit hex representation. The lazy mathematician would say “Well, then, we might as well say $ X \subset Y$, for this is the obvious way to view $ X$ as a set of hexadecimal numbers.” Of course there are other ways (try to think of one, and then try to find an infinite family of them!), but the point is that this is the only way that anyone really uses, and that the other ways are all just “natural relabelings” of this way.

The precise way to formulate this claim is as follows, and it holds for arbitrary sets and arbitrary injective functions. If $ g, g’: X \to Y$ are two such ways to inject $ X$ inside of $ Y$, then there is a function $ h: Y \to Y$ such that the composition $ hg$ is precisely the map $ g’$. If this is mysterious, we have some methods the reader can use to understand it more fully: give examples for simplified versions (what if there were only three colors?), draw pictures of “generic looking” set maps, and attempt a proof by direct implication.

Proof by Contrapositive

Often times in mathematics we will come across a statement we want to prove that looks like this:

If X does not have property A, then Y does not have property B.

Indeed, we already have: to prove a function $ f: X \to Y$ is injective we must prove:

If x is not equal to y, then f(x) is not equal to f(y).

A proof by direct implication can be quite difficult because the statement gives us very little to work with. If we assume that $ X$ does not have property $ A$, then we have nothing to grasp and jump-start our proof. The main (and in this author’s opinion, the only) benefit of a proof by contrapositive is that one can turn such a statement into a constructive one. That is, we can write “p implies q” as “not q implies not p” to get the equivalent claim:

If Y has property B then X has property A.

This rewriting is called the “contrapositive form” of the original statement. It’s not only easier to parse, but also probably easier to prove because we have something to grasp at from the beginning.

To the beginning mathematician, it may not be obvious that “if p then q” is equivalent to “if not q then not p” as logical statements. To show that they are requires a small detour into the idea of a “truth table.”

In particular, we have to specify what it means for “if p then q” to be true or false as a whole. There are four possibilities: p can be true or false, and q can be true or false. We can write all of these possibilities in a table.

p q

T T

T F

F T

F F

If we were to complete this table for “if p then q,” we’d have to specify exactly which of the four cases correspond to the statement being true. Of course, if the p part is true and the q part is true, then “p implies q” should also be true. We have seen this already in proof by direct implication. Next, if p is true and q is false, then it certainly cannot be the case that truth of p implies the truth of q. So this would be a false statement. Our truth table so far looks like

p q p->q

T T T

T F F

F T ?

F F ?

The next question is what to do if the premise p of “if p then q” is false. Should the statement as a whole be true or false? Rather then enter a belated philosophical discussion, we will zealously define an implication to be true if its hypothesis is false. This is a well-accepted idea in mathematics called vacuous truth. And although it seems to make awkward statements true (like “if 2 is odd then 1 = 0”), it is rarely a confounding issue (and more often forms the punchline of a few good math jokes). So we can complete our truth table as follows

p q p->q

T T T

T F F

F T T

F F T

Now here’s where contraposition comes into play. If we’re interested in determining when “not q implies not p” is true, we can add these to the truth table as extra columns:

p q p->q not q not p not q -> not p

T T T F F T

T F F T F F

F T T F T T

F F T T T T

As we can see, the two columns corresponding to “p implies q” and “not q implies not p” assume precisely the same truth values in all possible scenarios. In other words, the two statements are logically equivalent.

And so our proof technique for contrapositive becomes: rewrite the statement in its contrapositive form, and proceed to prove it by direct implication.

Examples and Exercises

Our first example will be completely straightforward and require nothing but algebra. Let’s show that the function $ f(x) = 7x – 4$ is injective. Contrapositively, we want to prove that if $ f(x) = f(x’)$ then $ x = x’$. Assuming the hypothesis, we start by supposing $ 7x – 4 = 7x’ – 4$. Applying algebra, we get $ 7x = 7x’$, and dividing by 7 shows that $x = x’$ as desired. So $ f$ is injective.

This example is important because if we tried to prove it directly, we might make the mistake of assuming algebra works with $ \neq$ the same way it does with equality. In fact, many of the things we take for granted about equality fail with inequality (for instance, if $ a \neq b$ and $ b \neq c$ it need not be the case that $ a \neq c$). The contrapositive method allows us to use our algebraic skills in a straightforward way.

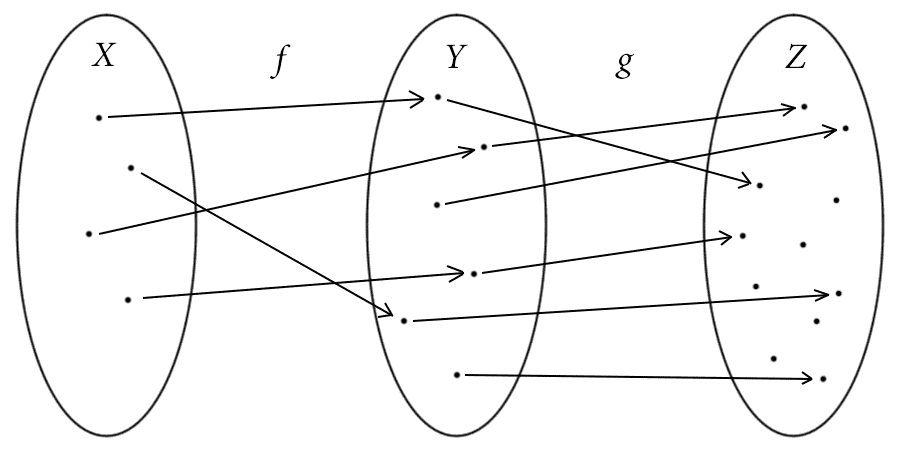

Next let’s prove that the composition of two injective functions is injective. That is, if $ f: X \to Y$ and $ g: Y \to Z$ are injective functions, then the composition $ gf : X \to Z$ defined by $ gf(x) = g(f(x))$ is injective.

In particular, we want to prove that if $ x \neq x’$ then $ g(f(x)) \neq g(f(x’))$. Contrapositively, this is the same as proving that if $ g(f(x)) = g(f(x’))$ then $ x=x’$. Well by the fact that $ g$ is injective, we know that (again contrapositively) whenever $ g(y) = g(y’)$ then $ y = y’$, so it must be that $ f(x) = f(x’)$. But by the same reasoning $ f$ is injective and hence $ x = x’$. This proves the statement.

This was a nice symbolic proof, but we can see the same fact in a picturesque form as well:

A composition of two injections is an injection.

If we maintain that any two arrows in the diagram can’t have the same head, then following two paths starting at different points in $ X$ will never land us at the same place in $ Z$. Since $ f$ is injective we have to travel to different places in $ Y$, and since $ g$ is injective we have to travel to different places in $ Z$. Unfortunately, this proof cannot replace the formal one above, but it can help us understand it from a different perspective (which can often make or break a mathematical idea).

Expanding upon this idea we give the reader a challenge: Let $ A, B, C$ be finite sets of the same size. Prove or disprove that if $ f: A \to B$ and $ g: B \to C$ are (arbitrary) functions, and if the composition $ gf$ is injective, then both of $ f, g$ must be injective.

Another exercise which has a nice contrapositive proof: prove that if $ A,B$ are finite sets and $ f:A \to B$ is an injection, then $ A$ has at most as many elements as $ B$. This one is particularly susceptible to a “picture proof” like the one above. Although the formal the formal name for the fact one uses to prove this is the pigeonhole principle, it’s really just a simple observation.

Aside from inventing similar exercises with numbers (e.g., if $ ab$ is odd then $ a$ is odd or $ b$ is odd), this is all there is to the contrapositive method. It’s just a direct proof disguised behind a fact about truth tables. Of course, as is usual in more advanced mathematical literature, authors will seldom announce the use of contraposition. The reader just has to be watchful enough to notice it.

Though we haven’t talked about either the real numbers $ \mathbb{R}$ nor proofs of existence or impossibility, we can still pose this interesting question: is there an injective function from $ \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{N}$? In truth there is not, but as of yet we don’t have the proof technique required to show it. This will be our next topic in the series: the proof by contradiction.

Until then!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.