In this post we’ll get a quick look at two ways to define a category as a type in ML. The first way will be completely trivial: we’ll just write it as a tuple of functions. The second will involve the terribly-named “functor” expression in ML, which allows one to give a bit more structure on data types.

The reader unfamiliar with the ML programming language should consult our earlier primer.

What Do We Want?

The first question to ask is “what do we want out of a category?” Recall from last time that a category is a class of objects, where each pair of objects is endowed with a set of morphisms. The morphisms were subject to a handful of conditions, which we paraphrase below:

- Composition has to make sense when it’s defined.

- Composition is associative.

- Every object has an identity morphism.

What is the computational heart of such a beast? Obviously, we can’t explicitly represent the class of objects itself. Computers are finite (or at least countable) beings, after all. And in general we can’t even represent the set of all morphisms explicitly. Think of the category $ \mathbf{Set}$: if $ A, B$ are infinite, then there are infinitely many morphisms (set-functions) $ A \to B$.

A subtler and more important point is that everything in our representation of a category needs to be a type in ML (for indeed, how can a program run without being able to understand the types involved). This nudges us in an interesting direction: if an object is a type, and a morphism is a type, then we might reasonably expect a composition function:

compose: 'arrow * 'arrow -> 'arrow

We might allow this function to raise an exception if the two morphisms are uncomposable. But then, of course, we need a way to determine if morphisms are composable, and this requires us to know what the source and target functions are.

source: 'arrow -> 'object

target: 'arrow -> 'object

We can’t readily enforce composition to be associative at this stage (or any), because morphisms don’t have any other manipulable properties. We can’t reasonably expect to be able to compare morphisms for equality, as we aren’t able to do this in $ \mathbf{Set}$.

But we can enforce the final axiom: that every object has an identity morphism. This would come in the form of a function which accepts as input an object and produces a morphism:

identity: 'object -> 'arrow

But again, we can’t necessarily enforce that identity behaves as its supposed to.

Even so, this should be enough to define a category. That is, in ML, we have the datatype

datatype ('object, 'arrow)Category =

category of ('arrow -> 'object) *

('arrow -> 'object) *

('object -> 'arrow) *

('arrow * 'arrow -> 'arrow)

Where we understand the first two functions to be source and target, and the third and fourth to be identity and compose, respectively.

Categories as Values

In order to see this type in action, we defined (and included in the source code archive for this post) a type for homogeneous sets. Since ML doesn’t support homogeneous lists natively, we’ll have to settle for a particular subcategory of $ \mathbf{Set}$. We’ll call it $ \mathbf{Set}_a$, the category whose objects are finite sets whose elements have type $ a$, and whose morphisms are again set-functions. Hence, we can define an object in this category as the ML type

'a Set

and an arrow as a datatype

datatype 'a SetMap = setMap of ('a Set) * ('a -> 'a) * ('a Set)

where the first object is the source and the second is the target (mirroring the notation $ A \to B$).

Now we must define the functions required for the data constructor of a Category. Source and target are trivial.

fun setSource(setMap(a, f, b)) = a

fun setTarget(setMap(a, f, b)) = b

And identity is equally natural.

fun setIdentity(aSet) = setMap(aSet, (fn x => x), aSet)

Finally, compose requires us to check for set equality of the relevant source and target, and compose the bundled set-maps. A few notational comments: the “o” operator does function composition in ML, and we defined “setEq” and the “uncomposable” exception elsewhere.

fun setCompose(setMap(b', g, c), setMap(a, f, b)) =

if setEq(b, b') then

setMap(a, (g o f), c)

else

raise uncomposable

Note that the second map in the composition order is the first argument to the function, as is standard in mathematical notation.

And now this category of finite sets is just the instantiation

val FiniteSets = category(setSource, setTarget, setIdentity, setCompose)

Oddly enough, this definition does not depend on the choice of a type for our sets! None of the functions we defined care about what the elements of sets are, so long as they are comparable for equality (in ML, such a type is denoted with two leading apostrophes: ”a).

This example is not very interesting, but we can build on it in two interesting ways. The first is to define the poset category of sets. Recall that the poset category of a set $ X$ has as objects subsets of $ X$ and there is a unique morphism from $ A \to B$ if and only if $ A \subset B$. There are two ways to model this in ML. The first is that we can assume the person constructing the morphisms is giving correct data (that is, only those objects which satisfy the subset relation). This would amount to a morphism just representing “nothing” except the pair $ (A,B)$. On the other hand, we may also require a function which verifies that the relation holds. That is, we could describe a morphism in this (or any) poset category as a datatype

datatype 'a PosetArrow = ltArrow of 'a * ('a -> 'a -> bool) * 'a

We still do need to assume the user is not creating multiple arrows with different functions (or we must tacitly call them all equal regardless of the function). We can do a check that the function actually returns true by providing a function for creating arrows in this particular poset category of a set with subsets.

exception invalidArrow

fun setPosetArrow(x)(y) = if subset(x)(y) then ltArrow(x, subset, y)

else raise invalidArrow

Then the functions defining a poset category are very similar to those of a set. The only real difference is in the identity and composition functions, and it is minor at that.

fun posetSource(ltArrow(x, f, y)) = x

fun posetTarget(ltArrow(x, f, y)) = y

fun posetIdentity(x) = ltArrow(x, (fn z => fn w => true), x)

fun posetCompose(ltArrow(b', g, c), ltArrow(a, f, b)) =

if b = b' then

ltArrow(a, (fn x => fn y => f(x)(b) andalso g(b)(y)), c)

else

raise uncomposable

We know that a set is always a subset of itself, so we can provide the constant true function in posetIdentity. In posetCompose, we assume things are transitive and provide the logical conjunction of the two verification functions for the pieces. Then the category as a value is

val Posets = category(posetSource, posetTarget, posetIdentity, posetCompose)

One will notice again that the homogeneous type of our sets is irrelevant. The poset category is parametric. To be completely clear, the type of the Poset category defined above is

('a Set, ('a Set)PosetArrow)Category

and so we can define a shortcut for this type.

type 'a PosetCategory = ('a Set, ('a Set)PosetArrow)Category

The only way we could make this more general is to pass the constructor for creating a particular kind of posetArrow (in our case, it just means fixing the choice of verification function, subset, for the more generic type constructor). We leave this as an exercise to the reader.

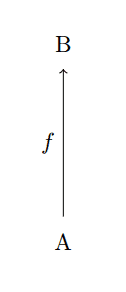

Our last example will return again to our abstract “diagram category.” Recall that if we fix an object $ A$ in a category $ \mathbf{C}$, the category $ \mathbf{C}_A$ has as objects the morphisms with fixed source $ A$,

vert-arrow

and the arrows are commutative diagrams

diagram-morphism

Lets fix $ A$ to be a set, and define a function to instantiate objects in this category:

fun makeArrow(fixedSet)(f)(target) = setMap(fixedSet, f, target)

That is, if I have a fixed set $ A$, I can call the function like so

val makeObject = makeArrow(fixedSet)

And use this function to create all of my objects. A morphism is then just a pair of set-maps with a connecting function. Note how similar this snippet of code looks structurally to the other morphism datatypes we’ve defined. This should reinforce the point that morphisms really aren’t any different in this abstract category!

datatype 'a TriangleDiagram =

triangle of ('a SetMap) * ('a -> 'a) * ('a SetMap)

And the corresponding functions and category instantiation are

fun triangleSource(triangle(x, f, y)) = x

fun triangleTarget(triangle(x, f, y)) = y

fun triangleIdentity(x) = triangle(x, (fn z => z), x)

fun triangleCompose(triangle(b', g, c), triangle(a, f, b)) =

if setEq(setTarget(b'))(setTarget(b)) then

triangle(a, (g o f), c)

else

raise uncomposable

val SetDiagrams =

category(triangleSource, triangleTarget, triangleIdentity, triangleCompose)

Notice how we cannot compare the objects in this category for equality! Indeed, two functions cannot be compared in ML, and the best we can do is compare the targets of these functions to ensure that the connecting morphisms can be composed. A malicious programmer might then be able to compose uncomposable morphisms, a devious and startling proposition.

Notice further how we can’t avoid using set-specific functions with our current definition of a category. What we could do instead is require a category to have a function which checks for composability. Then compose could be written in a more homogeneous (but not quite completely parametric fashion). The reader is welcome to try this on their own, but we’ll soon have a more organized way to do this later, when we package up a category into an ML structure.

Categories as Signatures

Let’s look at a more advanced feature of ML and see how we can apply it to representing categories in code. The idea is familiar to most Java and C++ programmers, and that is of an interface: the programmer specifies an abstract type which has specific functions attached to it, but does not implement those functions. Then some (perhaps different) programmer implements the interface by defining those functions for a concrete type.

For the reader who isn’t so interested in these features of ML, feel free to skip this section. We won’t be introducing any new examples of categories, just rephrasing what we’ve done above in a different way. It is also highly debatable whether this new way is actually any better (it’s certainly longer).

The corresponding concept in ML is called a signature (interface) and a structure (concrete instance). The only difference is that a structure is removed one step further from ML’s type system. This is in a sense necessary: a structure should be able to implement the requirements for many different signatures, and a signature should be able to have many different structures implement it. So there is no strict hierarchy of types to lean on (it’s just a many-to-many relationship).

On the other hand, not having any way to think of a structure as a type at all would be completely useless. The whole point is to be able to write function which manipulate a structure (concrete instance) by abstractly accessing the signature’s (interface’s) functions regardless of the particular implementation details. And so ML adds in another layer of indirection: the functor (don’t confuse this with categorical functors, which we haven’t talked abou yet). A functor in ML is a procedure which accepts as input a structure and produces as output another structure.

Let’s see this on a simple example. We can define a structure for “things that have magnitudes,” which as a signature would be

signature MAG_OBJ =

sig

type object

val mag : object -> int

end

This introduced a few new language forms: the “signature” keyword is like “fun” or “val,” it just declares the purpose of the statement as a whole. The “sig … end” expression is what actually creates the signature, and the contents are a list of type definitions, datatype definitions, and value/function type definitions. The reader should think of this as a named “type” for structures, analogous to a C struct.

To implement a signature in ML is to “ascribe” it. That is, we can create a structure that defines the functions laid out in a signature (and perhaps more). Here is an example of a structure for a mag object of integers:

structure IntMag : MAG_OBJ =

struct

type object = int

fun mag(x) = if x >= 0 then x else ~x

end

The colon is a type ascription, and at the compiler-level it goes through the types and functions defined in this structure and attempts to match them with the required ones from the MAG_OBJ signature. If it fails, it raises a compiler error. A more detailed description of this process can be found here. We can then use the structure as follows:

local open IntMag in

val y = ~7

val z = mag(y)

end

The open keyword binds all of the functions and types to the current environment (and so it’s naturally a bad idea to open structures in the global environment). The “local” construction is made to work specifically with open.

In any case, the important part about signatures and structures is that one can write functions which accept as input structures with a given signature and produce structures with other signatures. The name for this is a “functor,” but we will usually call it an “ML functor” to clarify that it is not a categorical functor (if you don’t know what a categorical functor is, don’t worry yet).

For example, here is a signature for a “distance object”

signature DIST_OBJ =

sig

type object

val dist: object * object -> int

end

And a functor which accepts as input a MAG_OBJ and creates a DIST_OBJ in a contrived and silly way.

functor MakeDistObj(structure MAG: MAG_OBJ) =

struct

type object = MAG.object

val dist = fn (x, y) =>

let

val v = MAG.mag(x) - MAG.mag(y)

in

if v > 0 then v else ~v

end

end

Here the argument to the functor is a structure called MAG, and we need to specify which type is to be ascribed to it; in this case, it’s a MAG_OBJ. Only things within the specified signature can be used within the struct expression that follows (if one needs a functor to accept as input something which has multiple type ascriptions, one can create a new signature that “inherits” from both). Then the right hand side of the functor is just a new structure definition, where the innards are allowed to refer to the properties of the given MAG_OBJ.

We could in turn define a functor which accepts a DIST_OBJ as input and produces as output another structure, and compose the two functors. This is started to sound a bit category-theoretical, but we want to remind the reader that a “functor” in category theory is quite different from a “functor” in ML (in particular, we have yet to mention the former, and the latter is just a mechanism to parameterize and modularize code).

In any case, we can do the same thing with a category. A general category will be represented by a signature, and a particular instance of a category is a structure with the implemented pieces.

signature CATEGORY =

sig

type object

type arrow

exception uncomposable

val source: arrow -> object

val target: arrow -> object

val identity: object -> arrow

val composable: arrow * arrow -> bool

val compose: arrow * arrow -> arrow

end

As it turns out, ML has an implementation of “sets” already, and it uses signatures. So instead of using our rinky-dink implementation of sets from earlier in this post, we can implement an instance of the ORD_KEY signature, and then call one of the many set-creating functors available to us. We’ll use an implementation based on red-black trees for now.

First the key:

structure OrderedInt : ORD_KEY =

struct

type ord_key = int

val compare = Int.compare

end

then the functor:

functor MakeSetCategory(structure ELT: ORD_KEY) =

struct

structure Set:ORD_SET = RedBlackSetFn(ELT)

type elt = ELT.ord_key

type object = Set.set

datatype arrow = function of object * (elt -> elt) * object

exception uncomposable

fun source(function(a, _, _)) = a

fun target(function(_, _, b)) = b

fun identity(a) = function(a, fn x => x, a)

fun composable(a,b) = Set.equal(a,b)

fun compose(function(b2, g, c), function(a, f, b1)) =

if composable(b1, b2) then

function(a, (g o f), c)

else

raise uncomposable

fun apply(function(a, f, b), x) = f(x)

end

The first few lines are the most confusing; the rest is exactly what we’ve seen from our first go-round of defining the category of sets. In particular, we call the RedBlackSetFn functor given the ELT structure, and it produces an implementation of sets which we name Set (and superfluously ascribe the type ORD_SET for clarity).

Then we define the “elt” type which is used to describe an arrow, the object type as the main type of an ORD_SET (see in this documentation that this is the only new type available in that signature), and the arrow type as we did earlier.

We can then define the category of sets with a given type as follows

structure IntSets = MakeSetCategory(structure ELT = OrderedInt)

The main drawback of this approach is that there’s so much upkeep! Every time we want to make a new kind of category, we need to define a new functor, and every time we want to make a new kind of category of sets, we need to implement a new kind of ORD_KEY. All of this signature and structure business can be quite confusing; it often seems like the compiler doesn’t want to cooperate when it should.

Nothing Too Shocking So Far

To be honest, we haven’t really done anything very interesting so far. We’ve seen a single definition (of a category), looked at a number of examples to gain intuition, and given a flavor of how these things will turn into code.

Before we finish, let’s review the pros and cons of a computational representation of category-theoretical concepts.

Pros:

- We can prove results by explicit construction (more on this next time).

- Different-looking categories are structurally similar in code.

- We can faithfully represent the idea of using (objects and morphisms of) categories as parameters to construct other categories.

- Writing things in code gives a fuller understanding of how they work.

Cons:

- All computations are finite, requiring us to think much harder than a mathematician about the definition of an object.

- The type system is too weak. we can’t enforce the axioms of a category directly or even ensure the functions act sensibly at all. As such, the programmer becomes responsible for any failure that occur from bad definitions.

- The type system is too strong. when we work concretely we are forced to work within homogeneous categories (e.g. of ‘a Set).

- We cannot ensure the ability to check equality on objects. This showed up in our example of diagram categories.

- The functions used in defining morphisms, e.g. in the category of sets, are somewhat removed from real set-functions. For example, nothing about category theory requires functions to be computable. Moreover, nothing about our implementation requires the functions to have any outputs at all (they may loop infinitely!). Moreover, it is not possible to ensure that any given function terminates on a given input set (this is the Halting problem).

This list looks quite imbalanced, but one might argue that the cons are relatively minor compared to the pros. In particular (and this is what this author hopes to be the case), being able to explicitly construct proofs to theorems in category theory will give one a much deeper understanding both of category theory and of programming. This is the ultimate prize.

Next time we will begin our investigation of universal properties (where the real fun starts), and we’ll use the programmatic constructions we laid out in this post to give constructive proofs that various objects are universal.

Until then!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.