This post is mainly mathematical. We left it out of our introduction to categories for brevity, but we should lay these definitions down and some examples before continuing on to universal properties and doing more computation. The reader should feel free to skip this post and return to it later when the words “isomorphism,” “monomorphism,” and “epimorphism” come up again. Perhaps the most important part of this post is the description of an isomorphism.

Isomorphisms, Monomorphisms, and Epimorphisms

Perhaps the most important paradigm shift in category theory is the focus on morphisms as the main object of study. In particular, category theory stipulates that the only knowledge one can gain about an object is in how it relates to other objects. Indeed, this is true in nearly all fields of mathematics: in groups we consider all isomorphic groups to be the same. In topology, homeomorphic spaces are not distinguished. The list goes on. The only way to do determine if two objects are “the same” is by finding a morphism with special properties. Barry Mazur gives a more colorful explanation by considering the meaning of the number 5 in his essay, “When is one thing equal to some other thing?” The point is that categories, more than existing to be a “foundation” for all mathematics as a formal system (though people are working to make such a formal system), exist primarily to “capture the essence” of mathematical discourse, as Mazur puts it. A category defines objects and morphisms, but literally all of the structure of a category lies in its morphisms. And so we study them.

The strongest kind of morphism we can consider is an isomorphism. An isomorphism is the way we say two objects in a category are “the same.” We don’t usually care whether two objects are equal, but rather whether some construction is unique up to isomorphism (more on that when we talk of universal properties). The choices made in defining morphisms in a particular category allow us to strengthen or weaken this idea of “sameness.”

Definition: A morphism $ f : A \to B$ in a category $ \mathbf{C}$ is an isomorphism if there exists a morphism $ g: B \to A$ so that both ways to compose $ f$ and $ g$ give the identity morphisms on the respective objects. That is,

$ gf = 1_A$ and $ fg = 1_B$.

The most basic (usually obvious, but sometimes very deep) question in approaching a new category is to ask what the isomorphisms are. Let us do this now.

In $ \mathbf{Set}$ the morphisms are set-functions, and it is not hard to see that any two sets of equal cardinality have a bijection between them. As all bijections have two-sided inverses, two objects in $ \mathbf{Set}$ are isomorphic if and only if they have the same cardinality. For example, all sets of size 10 are isomorphic. This is quite a weak notion of “sameness.” In contrast, there is a wealth of examples of groups of equal cardinality which are not isomorphic (the smallest example has cardinality 4). On the other end of the spectrum, a poset category $ \mathbf{Pos}_X$ has no isomorphisms except for the identity morphisms. The poset categories still have useful structure, but (as with objects within a category) the interesting structure is in how a poset category relates to other categories. This will become clearer later when we look at functors, but we just want to dissuade the reader from ruling out poset categories as uninteresting due to a lack of interesting morphisms.

Consider the category $ \mathbf{C}$ of ML types with ML functions as morphisms. An isomorphism in this category would be a function which has a two-sided inverse. Can the reader think of such a function?

Let us now move on to other, weaker properties of morphisms.

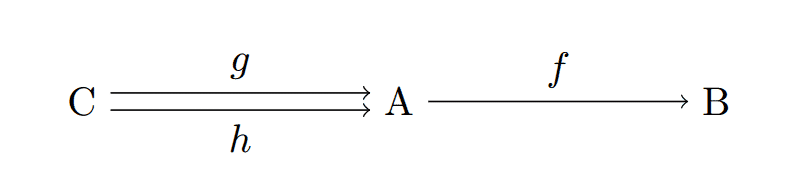

Definition: A morphism $ f: A \to B$ is a monomorphism if for every object $ C$ and every pair of morphisms $ g,h: C \to A$ the condition $ fg = fh$ implies $ g = h$.

The reader should parse this notation carefully, but truly think of it in terms of the following commutative diagram:

monomorphism-diagram

Whenever this diagram commutes and $ f$ is a monomorphism, then we conclude (by definition) that $ g=h$. Remember that a diagram commuting just means that all ways to compose morphisms (and arrive at morphisms with matching sources and targets) result in an identical morphism. In this diagram, commuting is the equivalent of claiming that $ fg = fh$, since there are only two nontrivial ways to compose.

The idea is that monomorphisms allow one to “cancel” $ f$ from the left side of a composition (although, confusingly, this means the cancelled part is on the right hand side of the diagram).

The corresponding property for cancelling on the right is defined identically.

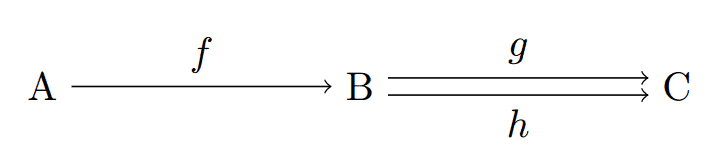

Definition: A morphism $ f: A \to B$ is an epimorphism if for every object $ C$ and every pair of morphism $ g,h: B \to C$ the condition $ gf = hf$ implies $ g = h$.

Again, the relevant diagram.

epimorphism-diagram

Whenever $ f$ is an epimorphism and this diagram commutes, we can conclude $ g=h$.

Now one of the simplest things one can do when considering a category is to identify the monomorphisms and epimorphisms. Let’s do this for a few important examples.

Monos and Epis in Various Categories

In the category $ \mathbf{Set}$, monomorphisms and epimorphisms correspond to injective and surjective functions, respectively. Lets see why this is the case for monomorphisms. Recall that an injective function $ f$ has the property that $ f(x) = f(y)$ implies $ x=y$. With this property we can show $ f$ is a monomorphism because if $ f(g(x)) = f(h(x))$ then the injective property gives us immediately that $ g(x) = h(x)$. Conversely, if $ f$ is a monomorphism and $ f(x) = f(y)$, we will construct a set $ C$ and two convenient functions $ g, h: C \to A$ to help us show that $ x=y$. In particular, pick $ C$ to be the one point set $ \left \{ c \right \}$, and define $ g(c) = x, h(c) = y$. Then as functions $ fg = fh$. Indeed, there is only one value in the domain, so saying this amounts to saying $ f(x) = fg(c) = fh(c) = f(y)$, which we know is true by assumption. By the monomorphism property $ g = h$, so $ x = g(c) = h(c) = y$.

Now consider epimorphisms. It is clear that a surjective map is an epimorphism, but the converse is a bit trickier. We prove by contraposition. Instead of now picking the “one-point set,” for our $ C$, we must choose something which is one element bigger than $ B$. In particular, define $ g, h : B \to B’$, where $ B’$ is $ B$ with one additional point $ x$ added (which we declare to not already be in $ B$). Then if $ f$ is not surjective, and there is some $ b_0 \in B$ which is missed by $ f$, we define $ g(b_0) = x$ and $ g(b) = b$ otherwise. We can also define $ h$ to be the identity on $ B$, so that $ gf = hf$, but $ g \neq h$. So epimorphisms are exactly the surjective set-maps.

There is one additional fact that makes the category of sets well-behaved: a morphism in $ \mathbf{Set}$ is an isomorphism if and only if it is both a monomorphism and an epimorphism. Indeed, isomorphisms are set-functions with two-sided inverses (bijections) and we know from classical set theory that bijections are exactly the simultaneous injections and surjections. A warning to the reader: not all categories are like this! We will see in a moment an example of a nontrivial category in which isomorphisms are not the same thing as simultaneous monomorphisms and epimorphisms.

The category $ \mathbf{Grp}$ is very similar to $ \mathbf{Set}$ in regards to monomorphisms and epimorphisms. The former are simply injective group homomorphisms, while the latter are surjective group homomorphisms. And again, a morphisms is an isomorphism if and only if it is both a monomorphism and an epimorphism. We invite the reader to peruse the details of the argument above and adapt it to the case of groups. In both cases, the hard decision is in choosing $ C$ when necessary. For monomorphisms, the “one-point group” does not work because we are constrained to send the identity to the identity in any group homomorphism. The fortuitous reader will avert their eyes and think about which group would work, and otherwise we suggest trying $ C = \mathbb{Z}$. After completing the proof, the reader will see that the trick is to find a $ C$ for which only one “choice” can be made. For epimorphisms, the required $ C$ is a bit more complex, but we invite the reader to attempt a proof to see the difficulties involved.

Why do these categories have the same properties but they are acquired in such different ways? It turns out that although these proofs seem different in execution, they are the same in nature, and they follow from properties of the category as a whole. In particular, the “one-point object” (a singleton set for $ \mathbf{Set}$ and $ \mathbb{Z}$ for $ \mathbf{Grp}$) is more categorically defined as the “free object on one generator.” We will discuss this more when we get to universal properties, but a “free object on $ n$ generators” is roughly speaking an object $ A$ for which any morphism with source $ A$ must make exactly $ n$ “choices” in its definition. With sets that means $ n$ choices for the images of elements, for groups that means $ n$ consistent choices for images of group elements. On the epimorphism side, the construction is a sort of “disjoint union object” which is correctly termed a “coproduct.” But momentarily putting aside all of this new and confusing terminology, let us see some more examples of morphisms in various categories.

Our recent primer on rings was well-timed, because the category $ \mathbf{Ring}$ of rings (with identity) is an example of a not-so-well-behaved category. As with sets and groups, we do have that monomorphisms are equivalent to injective ring homomorphisms, but the argument is trickier than it was for groups. It is not obvious which “convenient” object $ C$ to choose here, since maps $ \mathbb{Z} \to R$ yield no choices: 1 maps to 1, 0 maps to 0, and the properties of a ring homomorphism determine everything else (in fact, the abelian group structure and the fact that units are preserved is enough). This makes $ \mathbb{Z}$ into what’s called an “initial object” in $ \mathbf{Ring}$; more on that when we study universal properties. In fact, we invite the reader to return to this post after we talk about the universal property of polynomial rings. It turns out that $ \mathbb{Z}[x]$ is a suitable choice for $ C$, and the “choice” made is where to send the indeterminate $ x$.

On the other hand, things go awry when trying to apply analogous arguments to epimorphisms. While it is true that every surjective ring homomorphism is an epimorphism (it is already an epimorphism in $ \mathbf{Set}$, and the argument there applies), there are ring epimorphisms which are not surjections! Consider the inclusion map of rings $ i : \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Q}$. The map $ i$ is not surjective, but it is an epimorphism. Suppose $ g, h : \mathbb{Q} \to R$ are two parallel ring morphisms, and they agree on $ \mathbb{Z}$ (they will always do so, since there is only one ring homomorphism $ \mathbb{Z} \to R$). Then $ g,h$ must also agree on $ \mathbb{Q}$, because if $ p,q \in \mathbb{Z}$ with $ q \neq 0$, then

$$\displaystyle g(p/q) = g(p)g(q^{-1}) = g(p)g(q)^{-1} = h(p)h(q)^{-1} = h(p/q)$$Because the map above is also an injection, the category of rings is a very naturally occurring example of a category which has morphisms that are both epimorphisms and monomorphisms, but not isomorphisms.

There are instances in which monomorphisms and epimorphisms are trivial. Take, for instance any poset category. There is at most one morphism between any two objects, and so the conditions for an epimorphism and monomorphism vacuously hold. This is an extreme example of a time when simultaneous monomorphisms and epimorphisms are not the same thing as isomorphisms! The only isomorphisms in a poset category are the identity morphisms.

Morals about Good and Bad Categories

The inspection of epimorphisms and monomorphisms is an important step in the analysis of a category. It gives one insight into how “well-behaved” the category is, and picks out the objects which are special either for their useful properties or confounding trickery.

This reminds us of a quote of Alexander Grothendieck, one of the immortal gods of mathematics who popularized the use of categories in mainstream mathematics.

A good category containing some bad objects is preferable to a bad category containing only good objects.

I suppose the thesis here is that the having only “good” objects yields less interesting and useful structure, and that one should be willing to put up with the bad objects in order to have access to that structure.

Next time we’ll jump into a discussion of universal properties, and start constructing some programs to prove that various objects satisfy them.

Until then!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.