Previously in this series we’ve seen the definition of a category and a bunch of examples, basic properties of morphisms, and a first look at how to represent categories as types in ML. In this post we’ll expand these ideas and introduce the notion of a universal property. We’ll see examples from mathematics and write some programs which simultaneously prove certain objects have universal properties and construct the morphisms involved.

A Grand Simple Thing

One might go so far as to call universal properties the most important concept in category theory. This should initially strike the reader as odd, because at first glance universal properties are so succinctly described that they don’t seem to be very interesting. In fact, there are only two universal properties and they are that of being initial and final.

Definition: An object $ A$ in a category $ \mathbf{C}$ is called initial if for every object $ B$ there is a unique morphism $ A \to B$. An object $ Z$ is called final if for every object $ B$ there is a unique morphism $ B \to Z$. If an object satisfies either of these properties, it is called universal. If an object satisfies both, it is called a zero object.

In both cases, the existence of a unique morphism is the same as saying the relevant Hom set is a singleton (i.e., for initial objects $ A$, the Hom set $ \textup{Hom}_{\mathbf{C}}(A,B)$ consists of a single element). There is one and only one morphism between the two objects. In the particular case of $ \textup{Hom}(A,A)$ when $ A$ is initial (or final), the definition of a category says there must be at least one morphism, the identity, and the universal property says there is no other.

There’s only one way such a simple definition could find fruitful applications, and that is by cleverly picking categories. Before we get to constructing interesting categories with useful universal objects, let’s recognize some universal objects in categories we already know.

In $ \mathbf{Set}$ the single element set is final, but not initial; there is only one set-function to a single-element set. It is important to note that the single-element set is far from unique. There are infinitely many (uncountably many!) singleton sets, but as we have already seen all one-element sets are isomorphic in $ \mathbf{Set}$ (they all have the same cardinality). On the other hand, the empty set is initial, since the “empty function” is the only set-mapping from the empty set to any set. Here the initial object truly is unique, and not just up to isomorphism.

It turns out universal objects are always unique up to isomorphism, when they exist. Here is the official statement.

Proposition: If $ A, A’$ are both initial in $ \mathbf{C}$, then $ A \cong A’$ are isomorphic. If $ Z, Z’$ are both final, then $ Z \cong Z’$.

Proof. Recall that a mophism $ f: A \to B$ is an isomorphism if it has a two sided inverse, a $ g:B \to A$ so that $ gf = 1_A$ and $ fg=1_B$ are the identities. Now if $ A,A’$ are two initial objects there are unique morphisms $ f : A \to A’$ and $ g: A’ \to A$. Moreover, these compose to be morphisms $ gf: A \to A$. But since $ A$ is initial, the only morphism $ A \to A$ is the identity. The situation for $ fg : A’ \to A’$ is analogous, and so these morphisms are actually inverses of each other, and $ A, A’$ are isomorphic. The proof for final objects is identical. $ \square$

Let’s continue with examples. In the category of groups, the trivial group $ \left \{ 1 \right \}$ is both initial and final, because group homomorphisms must preserve the identity element. Hence the trivial group is a zero object. Again, “the” trivial group is not unique, but unique up to isomorphism.

In the category of types with computable (halting) functions as morphisms, the null type is final. To be honest, this depends on how we determine whether two computable functions are “equal.” In this case, we only care about the set of inputs and outputs, and for the null type all computable functions have the same output: null.

Partial order categories are examples of categories which need not have universal objects. If the partial order is constructed from subsets of a set $ X$, then the initial object is the empty set (by virtue of being a subset of every set), and $ X$ as a subset of itself is obviously final. But there are other partial orders, such as inequality of integers, which have no “smallest” or “largest” objects. Partial order categories which have particularly nice properties (such as initial and final objects, but not quite exactly) are closely related to the concept of a domain in denotational semantics, and the language of universal properties is relevant to that discussion as well.

The place where universal properties really shine is in defining new constructions. For instance, the direct product of sets is defined by the fact that it satisfies a universal property. Such constructions abound in category theory, and they work via the ‘diagram categories’ we defined in our introductory post. Let’s investigate them now.

Quotients

Let’s recall the classical definition from set theory of a quotient. We described special versions of quotients in the categories of groups and topological spaces, and we’ll see them all unified via the universal property of a quotient in a moment.

Definition: An equivalence relation on a set $ X$ is a subset of the set product $ \sim \subset X \times X$ which is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. The quotient set $ X / \sim$ is the set of equivalence classes on $ X$. The canonical projection $ \pi : X \to X/\sim$ is the map sending $ x$ to its equivalence class under $ \sim$.

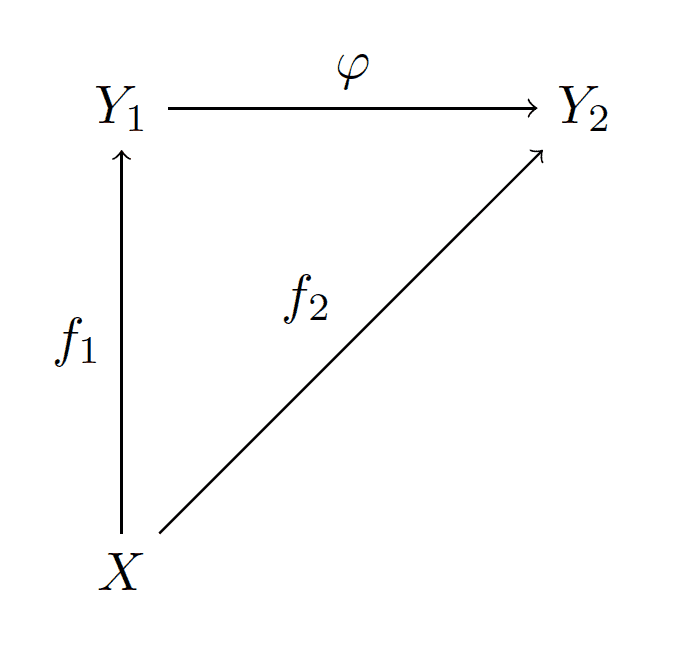

The quotient set $ X / \sim$ can also be described in terms of a special property: it is the “largest” set which agrees with the equivalence relation $ \sim$. On one hand, it is the case that whenever $ a \sim b$ in $ X$ then $ \pi(a) = \pi(b)$. Moreover, for any set $ Y$ and any map $ g: X \to Y$ which equates equivalent things ($ g(a) = g(b)$ for all $ a \sim b$), then there is a unique map $ f : X/\sim \to Y$ such that $ f \pi = g$. This word salad is best translated into a diagram.

universal-quotient

Here we use a dashed line to assert the existence of a morphism (once we’ve proven such a morphism exists, we use a solid line instead), and the symbol $ \exists !$ signifies existence ($ \exists$) and uniqueness (!).

We can prove this explicitly in the category $ \mathbf{Set}$. Indeed, if $ g$ is any map such that $ g(a) = g(b)$ for all equivalent $ a,b \in X$, then we can define $ f$ as follows: for any $ a \in X$ whose equivalence class is denoted by $ [a]$ in $ X / \sim$, and define $ f([a]) = g(a)$. This map is well defined because if $ a \sim b$, then $ f([a]) = g(a) = g(b) = f([b])$. It is unique because if $ f \pi = g = h \pi$ for some other $ h: X / \sim \to Y$, then $ h([x]) = g(x) = f([x])$; this is the only possible definition.

Now the “official” way to state this universal property is as follows:

The quotient set $ X / \sim$ is universal with respect to the property of mapping $ X$ to a set so that equivalent elements have the same image.

But as we said earlier, there are only two kinds of universal properties: initial and final. Now this $ X / \sim$ looks suspiciously like an initial object ($ f$ is going from $ X / \sim$, after all), but what exactly is the category we’re considering? The trick to dissecting this sentence is to notice that this is not a statement about just $ X / \sim$, but of the morphism $ \pi$.

That is, we’re considering a diagram category. In more detail: fix an object $ X$ in $ \mathbf{Set}$ and an equivalence relation $ \sim$ on $ X$. We define a category $ \mathbf{Set}_{X,\sim}$ as follows. The objects in the category are morphisms $ f:X \to Y$ such that $ a \sim b$ in $ X$ implies $ f(a) = f(b)$ in $ Y$. The morphisms in the category are commutative diagrams

diagrams-quotient-category

Here $ f_1, f_2$ need to be such that they send equivalent things to equal things (or they wouldn’t be objects in the category!), and by the commutativity of the diagram $ f_2 = \varphi f_1$. Indeed, the statement about quotients is that $ \pi : X \to X / \sim$ is an initial object in this category. In fact, we have already proved it! But note the abuse of language in our offset statement above: it’s not really $ X / \sim$ that is the universal object, but $ \pi$. Moreover, the statement itself doesn’t tell us what category to inspect, nor whether we care about initial or final objects in that category. Unfortunately this abuse of language is widespread in the mathematical world, and for arguably good reason. Once one gets acquainted with these kinds of constructions, reading between the limes becomes much easier and it would be a waste of time to spell it out. After all, once we understand $ X / \sim$ there is no “obvious” choice for a map $ X \to X / \sim$ except for the projection $ \pi$. This is how $ \pi$ got its name, the *canonical projection.

Two last bits of terminology: if $ \mathbf{C}$ is any category whose objects are sets (and hence, where equivalence relations make sense), we say that $ \mathbf{C}$ has quotients if for every object $ X$ there is a morphism $ \pi$ satisfying the universal property of a quotient. Another way to state the universal property is to say that all maps respecting the equivalence structure factor through the quotient, in the sense that we get a diagram like the one above.

What is the benefit of viewing $ X / \sim$ by its universal property? For one, the set $ X / \sim$ is unique up to isomorphism. That is, if any other pair $ (Z, g)$ satisfies the same property, we automatically get an isomorphism $ X / \sim \to Z$. For instance, if $ \sim$ is defined via a function $ f : X \to Y$ (that is, $ a \sim b$ if $ f(a) = f(b)$), then the pair $ (\textup{im}(f), f)$ satisfies the universal property of a quotient. This means that we can “decompose” any function into three pieces:

$$\displaystyle X \to X / \sim \to \textup{im}(f) \to Y$$The first map is the canonical projection, the second is the isomorphism given by the universal property of the quotient, and the last is the inclusion map into $ Y$. In a sense, all three of these maps are “canonical.” This isn’t so magical for set-maps, but the same statement (and essentially the same proof) holds for groups and topological spaces, and are revered as theorems. For groups, this is called The First Isomorphism Theorem, but it’s essentially the claim that the category of groups has quotients.

This is getting a bit abstract, so let’s see how the idea manifests itself as a program. In fact, it’s embarrassingly simple. Using our “simpler” ML definition of a category from last time, the constructive proof that quotient sets satisfy the universal property is simply a concrete version of the definition of $ f$ we gave above. In code,

fun inducedMapFromQuotient(setMap(x, pi, q), setMap(x, g, y)) =

setMap(q, (fn a => g(representative(a))), y)

That is, once we have $ \pi$ and $ X / \sim$ defined for our given equivalence relation, this function accepts as input any morphism $ g$ and produces the uniquely defined $ f$ in the diagram above. Here the “representative” function just returns an arbitrary element of the given set, which we added to the abstract datatype for sets. If the set $ X$ is empty, then all functions involved will raise an “empty” exception upon being called, which is perfectly fine. We leave the functions which explicitly construct the quotient set given $ X, \sim$ as an exercise to the reader.

Products and Coproducts

Just as the concept of a quotient set or quotient group can be generalized to a universal property, so can the notion of a product. Again we take our intuition from $ \mathbf{Set}$. There the product of two sets $ X,Y$ is the set of ordered pairs

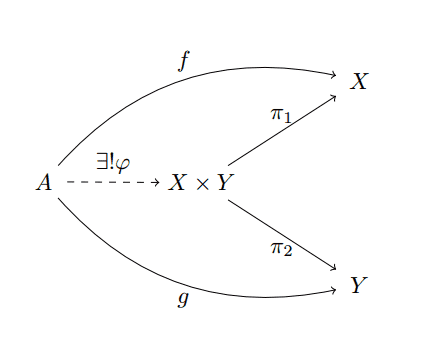

$$\displaystyle X \times Y = \left \{ (x,y) : x \in X, y \in Y \right \}$$But as with quotients, there’s much more going on and the key is in the morphisms. Specifically, there are two obvious choices for morphisms $ X \times Y \to X$ and $ X \times Y \to Y$. These are the two projections onto the components, namely $ \pi_1(x,y) = x$ and $ \pi_2(x,y) = y$. These projections are also called “canonical projections,” and they satisfy their own universal property.

The product of sets is universal with respect to the property of having two morphisms to its factors.

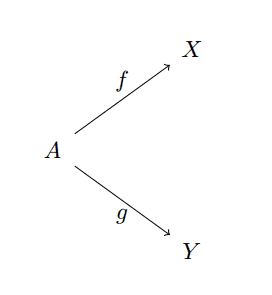

Indeed, this idea is so general that it can be formulated in any category, not just categories whose objects are sets. Let $ X,Y$ be two fixed objects in a category $ \mathbf{C}$. Should it exist, the product $ X \times Y$ is defined to be a final object in the following diagram category. This category has as objects pairs of morphisms

product-diagram-object

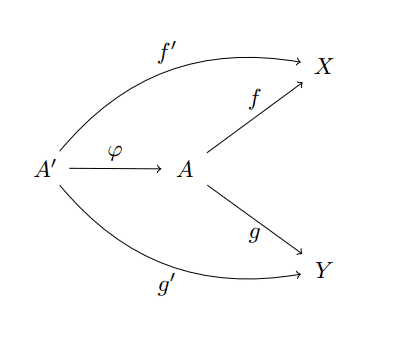

and as morphisms it has commutative diagrams

product-diagram-morphism

In words, to say products are final is to say that for any object in this category, there is a unique map $ \varphi$ that factors through the product, so that $ \pi_1 \varphi = f$ and $ \pi_2 \varphi = g$. In a diagram, it is to claim the following commutes:

product-universal-property

If the product $ X \times Y$ exists for any pair of objects, we declare that the category $ \mathbf{C}$ has products.

Indeed, many familiar product constructions exist in pure mathematics: sets, groups, topological spaces, vector spaces, and rings all have products. In fact, so does the category of ML types. Given two types ‘a and ‘b, we can form the (aptly named) product type ‘a * ‘b. The canonical projections exist because ML supports parametric polymorphism. They are

fun leftProjection(x,y) = x

fun rightProjection(x,y) = y

And to construct the unique morphism to the product,

fun inducedMapToProduct(f,g) = fn a => (f(a), g(a))

We leave the uniqueness proof to the reader as a brief exercise.

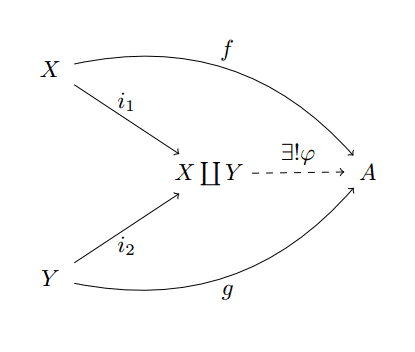

There is a similar notion called a coproduct, denoted $ X \coprod Y$, in which everything is reversed: the arrows in the diagram category go to $ X \coprod Y$ and the object is initial in the diagram category. Explicitly, for a fixed $ X, Y$ the objects in the diagram category are again pairs of morphisms, but this time with arrows going to the central object

coprod-diagram-object

The morphisms are again commutative diagrams, but with the connecting morphism going away from the central object

coprod-diagram-morphism

And a coproduct is defined to be an initial object in this category. That is, a pair of morphisms $ i_1, i_2$ such that there is a unique connecting morphism in the following diagram.

coprod-universal-property

Coproducts are far less intuitive than products in their concrete realizations, but the universal property is no more complicated. For the category of sets, the coproduct is a disjoint union (in which shared elements of two sets $ X, Y$ are forcibly considered different), and the canonical morphisms are “inclusion” maps (hence the switch from $ \pi$ to $ i$ in the diagram above). Specifically, if we define the coproduct

$$\displaystyle X \coprod Y = (X \times \left \{ 1 \right \}) \cup (Y \times \left \{ 2 \right \})$$as the set of “tagged” elements (the right entry in a tuple signifies which piece of the coproduct the left entry came from), then the inclusion maps $ i_1(x) = (x,1)$ and $ i_2(y) = (y,2)$ are the canonical morphisms.

There are similar notions of disjoint unions for topological spaces and graphs, which are their categories’ respective coproducts. However, in most categories the coproducts are dramatically different from “unions.” In group theory, it is a somewhat complicated object known as the free product. We mentioned free products in our hasty discussion of the fundamental group, but understanding why and where free groups naturally occur is quite technical. Similarly, coproducts of vector spaces (or $ R$-modules) are more like a product, with the stipulation that at most finitely many of the entries of a tuple are nonzero (e.g., formal linear combinations of things from the pieces). Even without understanding these examples, the reader should begin to believe that relatively simple universal properties can yield very useful objects with potentially difficult constructions in specific categories. The ubiquity of the concepts across drastically different fields of mathematics is part of why universal properties are called “universal.”

Luckily, the category of ML types has a nice coproduct which feels like a union, but it is not supported as a “native” language feature like products types are. Specifically, given two types ‘a, ‘b we can define the “coproduct type”

datatype ('a, 'b)Coproduct = left of 'a | right of 'b

Let’s prove this is actually a coproduct: fix two types ‘a and ‘b, and let $ i_1, i_2$ be the functions

fun leftInclusion(x) = left(x)

fun rightInclusion(y) = right(y)

Then given any other pair of functions $ f,g$ which accept as input types ‘a and ‘b, respectively, there is a unique function $ \varphi$ operating on the coproduct type. We construct it as follows.

fun inducedCoproductMap(f,g) =

let

theMap(left(a)) = f(a)

theMap(right(b)) = g(b)

in

theMap

end

The uniqueness of this construction is self-evident. This author finds it fascinating that these definitions are so deep and profound (indeed, category theory is heralded as the queen of abstraction), but their realizations are trivially obvious to the working programmer. Perhaps this is a statement about how well-behaved the category of ML types is.

Continuing On

So far we have seen three relatively simple examples of universal properties, and explored how they are realized in some categories. We should note before closing two things. The first is that not every category has objects with these universal properties. Unfortunately poset categories don’t serve as a good counterexample for this (they have both products and coproducts; what are they?), but it may be the case that in some categories only some pairs of objects have products or coproducts, while others do not.

Second, there are many more universal properties that we haven’t covered here. For instance, the notion of a limit is a universal property, as is the notion of a “free” object. There are kernels, pull-backs, equalizers, and many other ad-hoc universal properties without names. And for every universal property there is a corresponding “dual” property that results from reversing the arrows in every diagram, as we did with coproducts. We will visit the relevant ones as they come up in our explorations.

In the next few posts we’ll encounter functors and the concept of functoriality, and start asking some poignant questions about familiar programmatic constructions.

Until then!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.