Finding solutions to systems of polynomial equations is one of the oldest and deepest problems in all of mathematics. This is broadly the domain of algebraic geometry, and mathematicians wield some of the most sophisticated and abstract tools available to attack these problems.

The elliptic curve straddles the elementary and advanced mathematical worlds in an interesting way. On one hand, it’s easy to describe in elementary terms: it’s the set of solutions to a cubic function of two variables. But despite how simple they seem deep theorems govern their behavior, and many natural questions about elliptic curves are still wide open. Since elliptic curves provide us with some of the strongest and most widely used encryption protocols, understanding elliptic curves more deeply would give insight into the security (or potential insecurity) of these protocols.

Our first goal in this series is to treat elliptic curves as mathematical objects, and derive the elliptic curve group as the primary object of study. We’ll see what “group” means next time, and afterward we’ll survey some of the vast landscape of unanswered questions. But this post will be entirely elementary, and will gently lead into the natural definition of the group structure on an elliptic curve.

Elliptic Curves as Equations

The simplest way to describe an elliptic curve is as the set of all solutions to a specific kind of polynomial equation in two real variables, $ x,y$. Specifically, the equation has the form:

$$\displaystyle y^2 = x^3 + ax + b$$Where $ a,b$ are real numbers such that

$$\displaystyle -16(4a^3 + 27b^2) \neq 0$$One would naturally ask, “Who the hell came up with that?” A thorough answer requires a convoluted trip through 19th and 20th-century mathematical history, but it turns out that this is a clever form of a very natural family of equations. We’ll elaborate on this in another post, but for now we can give an elementary motivation.

Say you have a pyramid of spheres whose layers are squares, like the one below

pyramid-spheres

We might wonder when it’s the case that we can rearrange these spheres into a single square. Clearly you can do it for a pyramid of height 1 because a single ball is also a 1×1 square (and one of height zero if you allow a 0x0 square). But are there any others?

This question turns out to be a question about an elliptic curve. First, recall that the number of spheres in such a pyramid is given by

$$\displaystyle 1 + 4 + 9 + 16 + \dots + n^2 = \frac{n(n+1)(2n+1)}{6}$$And so we’re asking if there are any positive integers $ y$ such that

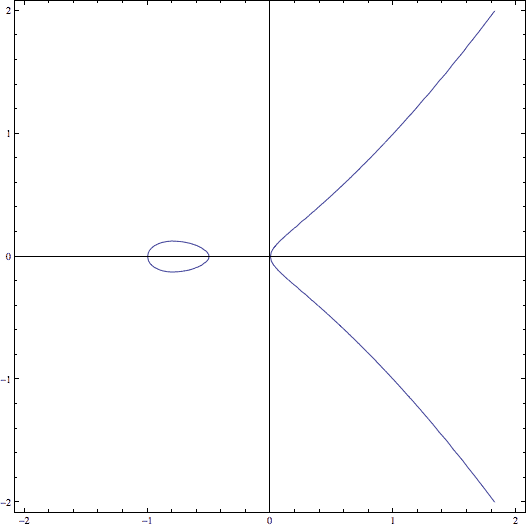

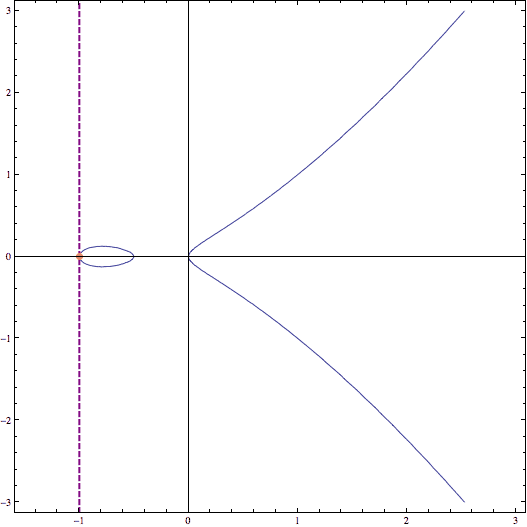

$$\displaystyle y^2 = \frac{x(x+1)(2x+1)}{6}$$Here is a graph of this equation in the plane. As you admire it, though, remember that we’re chiefly interested in integer solutions.

pyramid-ec

The equation doesn’t quite have the special form we mentioned above, but the reader can rest assured (and we’ll prove it later) that one can transform our equation into that form without changing the set of solutions. In the meantime let’s focus on the question: are there any integer-valued points on this curve besides $ (0,0)$ and $ (1,1)$? The method we use to answer this question comes from ancient Greece, and is due to Diophantus. The idea is that we can use the two points we already have to construct a third point. This method is important because it forms the basis for our entire study of elliptic curves.

Take the line passing through $ (0,0)$ and $ (1,1)$, given by the equation $ y = x$, and compute the intersection of this line and the original elliptic curve. The “intersection” simply means to solve both equations simultaneously. In this case it’s

$$\begin{aligned} y^2 &= \frac{x(x+1)(2x+1)}{6} \\\ y &= x \end{aligned}$$It’s clear what to do: just substitute the latter in for the former. That is, solve

$$\displaystyle x^2 = \frac{x(x+1)(2x+1)}{6}$$Rearranging this into a single polynomial and multiplying through by 3 gives

$$\displaystyle x^3 – \frac{3x^2}{2} + \frac{x}{2} = 0$$Factoring cubics happens to be easy, but let’s instead use a different trick that will come up again later. Let’s use a fact that is taught in elementary algebra and precalculus courses and promptly forgotten, that the sum of the roots of any polynomial is $ \frac{-a_{n-1}}{a_n}$, where $ a_{n}$ is the leading coefficient and $ a_{n-1}$ is the next coefficient. Here $ a_n = 1$, so the sum of the roots is $ 3/2$. This is useful because we already know two roots, namely the solutions 0 and 1 we used to define the system of equations in the first place. So the third root satisfies

$$\displaystyle r + 0 + 1 = \frac{3}{2}$$And it’s $ r = 1/2$, giving the point $ (1/2, 1/2)$ since the line was $ y=x$. Because of the symmetry of the curve, we also get the point $ (1/2, -1/2)$.

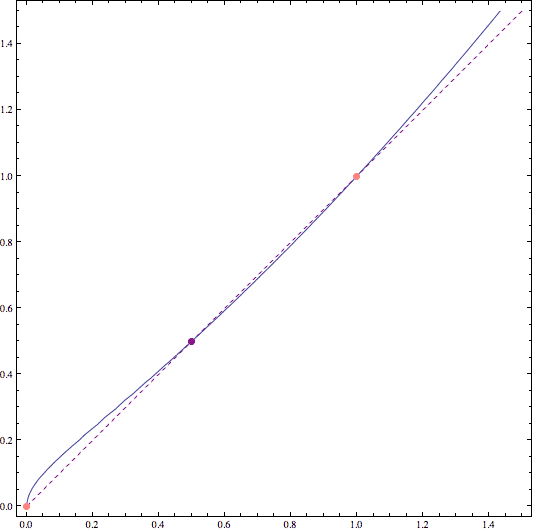

Here’s a zoomed-in picture of what we just did to our elliptic curve. We used the two pink points (which gave us the dashed line) to find the purple point.

line-intersection-example

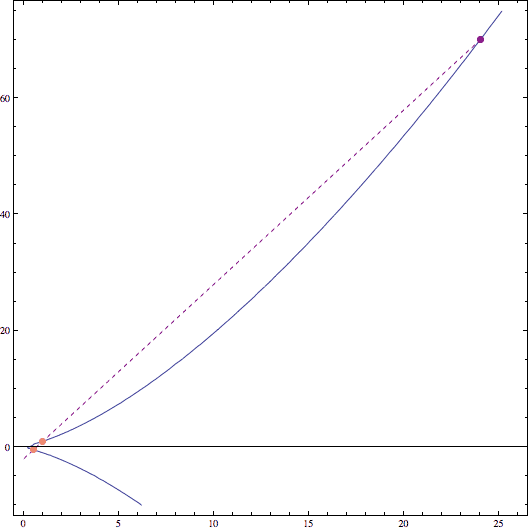

The bad news is that these two new points don’t have integer coordinates. So it doesn’t answer our question. The good news is that now we have more points! So we can try this trick again to see if it will give us still more points, and hope to find some that are integer valued. (It sounds like a hopeless goal, but just hold out a bit longer). If we try this trick again using $ (1/2, -1/2)$ and $ (1,1)$, we get the equation

$$\displaystyle (3x – 2)^2 = \frac{x(x+1)(2x+1)}{6}$$And redoing all the algebraic steps we did before gives us the solution $ x=24, y=70$. In other words, we just proved that

$$\displaystyle 1^2 + 2^2 + \dots + 24^2 = 70^2$$Great! Here’s another picture showing what we just did.

line-intersection-example-2

In reality we don’t care about this little puzzle. Its solution might be a fun distraction (and even more distracting: try to prove there aren’t any other integer solutions), but it’s not the real treasure. The mathematical gem is the method of finding the solution. We can ask the natural question: if you have two points on an elliptic curve, and you take the line between those two points, will you always get a third point on the curve?

Certainly the answer is no. See this example of two points whose line is vertical.

vertical-line

But with some mathematical elbow grease, we can actually force it to work! That is, we can define things just right so that the line between any two points on an elliptic curve will always give you another point on the curve. This sounds like mysterious black magic, but it lights the way down a long mathematical corridor of new ideas, and is required to make sense of using elliptic curves for cryptography.

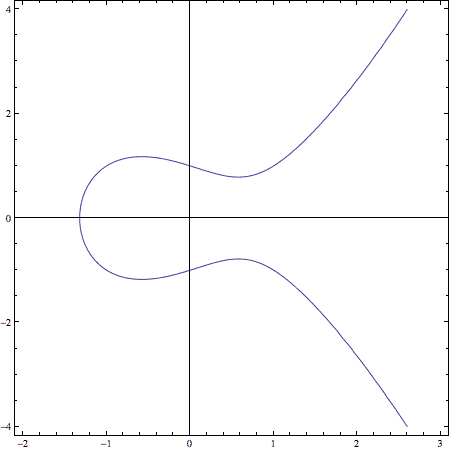

Shapes of Elliptic Curves

Before we continue, let’s take a little detour to get a good feel for the shapes of elliptic curves. We have defined elliptic curves by a special kind of equation (we’ll give it a name in a future post). During most of our study we won’t be able to make any geometric sense of these equations. But for now, we can pretend that we’re working over real numbers and graph these equations in the plane.

Elliptic curves in the form $ y^2 = x^3 + ax + b$ have a small handful of different shapes that we can see as $ a,b$ vary:

ECdynamics1](/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/ecdynamics1.gif?resize=450%2C465)](/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/ecdynamics1.gif)[

canonical-EC

So in the next post we’ll roll up our sleeves and see exactly how “drawing lines” can be turned into an algebraic structure on an elliptic curve.

Until then!