Last time we saw the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol, and discussed the discrete logarithm problem and the related Diffie-Hellman problem, which form the foundation for the security of most protocols that use elliptic curves. Let’s continue our journey to investigate some more protocols.

Just as a reminder, the Python implementations of these protocols are not at all meant for practical use, but for learning purposes. We provide the code on this blog’s Github page, but for the love of security don’t actually use them.

Shamir-Massey-Omura

Recall that there are lots of ways to send encrypted messages if you and your recipient share some piece of secret information, and the Diffie-Hellman scheme allows one to securely generate a piece of shared secret information. Now we’ll shift gears and assume you don’t have a shared secret, nor any way to acquire one. The first cryptosystem in that vein is called the Shamir-Massey-Omura protocol. It’s only slightly more complicated to understand than Diffie-Hellman, and it turns out to be equivalently difficult to break.

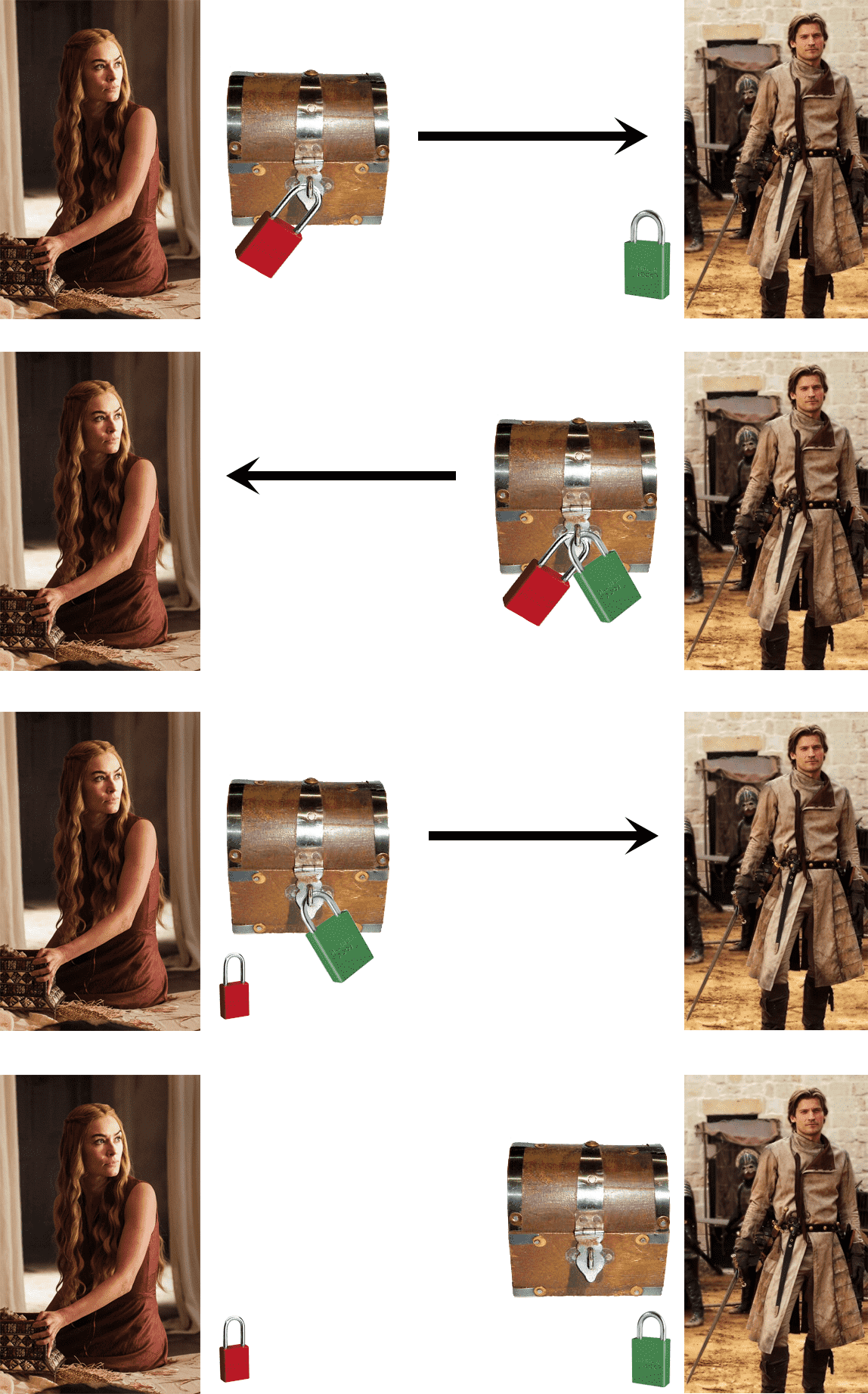

The idea is best explained by metaphor. Alice wants to send a message to Bob, but all she has is a box and a lock for which she has the only key. She puts the message in the box and locks it with her lock, and sends it to Bob. Bob can’t open the box, but he can send it back with a second lock on it for which Bob has the only key. Upon receiving it, Alice unlocks her lock, sends the box back to Bob, and Bob can now open the box and retrieve the message.

To celebrate the return of Game of Thrones, we’ll demonstrate this protocol with an original Lannister Infographic™.

Assuming the box and locks are made of magical unbreakable Valyrian steel, nobody but Jamie will be able to read the message.

Now fast forward through the enlightenment, industrial revolution, and into the age of information. The same idea works, and it’s significantly faster over long distances. Let $ C$ be an elliptic curve over a finite field $ k$ (we’ll fix $ k = \mathbb{Z}/p$ for some prime $ p$, though it works for general fields too). Let $ n$ be the number of points on $ C$.

Alice’s message is going to be in the form of a point $ M$ on $ C$. She’ll then choose her secret integer $ 0 < s_A < p$ and compute $ s_AM$ (locking the secret in the box), sending the result to Bob. Bob will likewise pick a secret integer $ s_B$, and send $ s_Bs_AM$ back to Alice.

Now the unlocking part: since $ s_A \in \mathbb{Z}/p$ is a field, Alice can “unlock the box” by computing the inverse $ s_A^{-1}$ and computing $ s_BM = s_A^{-1}s_Bs_AM$. Now the “box” just has Bob’s lock on it. So Alice sends $ s_BM$ back to Bob, and Bob performs the same process to evaluate $ s_B^{-1}s_BM = M$, thus receiving the message.

Like we said earlier, the security of this protocol is equivalent to the security of the Diffie-Hellman problem. In this case, if we call $ z = s_A^{-1}$ and $ y = s_B^{-1}$, and $ P = s_As_BM$, then it’s clear that any eavesdropper would have access to $ P, zP$, and $ yP$, and they would be tasked with determining $ zyP$, which is exactly the Diffie-Hellman problem.

Now Alice’s secret message comes in the form of a point on an elliptic curve, so how might one translate part of a message (which is usually represented as an integer) into a point? This problem seems to be difficult in general, and there’s no easy answer. Here’s one method originally proposed by Neal Koblitz that uses a bit of number theory trickery.

Let $ C$ be given by the equation $ y^2 = x^3 + ax + b$, again over $ \mathbb{Z}/p$. Suppose $ 0 \leq m < p/100$ is our message. Define for any $ 0 \leq j < 100$ the candidate $ x$-points $ x_j = 100m + j$. Then call our candidate $ y^2$-values $ s_j = x_j^3 + ax_j + b$. Now for each $ j$ we can compute $ x_j, s_j$, and so we’ll pick the first one for which $ s_j$ is a square in $ \mathbb{Z}/p$ and we’ll get a point on the curve. How can we tell if $ s_j$ is a square? One condition is that $ s_j^{(p-1)/2} \equiv 1 \mod p$. This is a basic fact about quadratic residues modulo primes; see these notes for an introduction and this Wikipedia section for a dense summary.

Once we know it’s a square, we can compute the square root depending on whether $ p \equiv 1 \mod 4$ or $ p \equiv 3 \mod 4$. In the latter case, it’s just $ s_j^{(p+1)/4} \mod p$. Unfortunately the former case is more difficult (really, the difficult part is $ p \equiv 1 \mod 8$). You can see Section 1.5 of this textbook for more details and three algorithms, or you could just pick primes congruent to 3 mod 4.

I have struggled to find information about the history of the Shamir-Massey-Omura protocol; every author claims it’s not widely used in practice, and the only reason seems to be that this protocol doesn’t include a suitable method for authenticating the validity of a message. In other words, some “man in the middle” could be intercepting messages and tricking you into thinking he is your intended recipient. Coupling this with the difficulty of encoding a message as a point seems to be enough to make cryptographers look for other methods. Another reason could be that the system was patented in 1982 and is currently held by SafeNet, one of the US’s largest security providers. All of their products have generic names so it’s impossible to tell if they’re actually using Shamir-Massey-Omura. I’m no patent lawyer, but it could simply be that nobody else is allowed to implement the scheme.

Digital Signatures

Indeed, the discussion above raises the question: how does one authenticate a message? The standard technique is called a digital signature, and we can implement those using elliptic curve techniques as well. To debunk the naive idea, one cannot simply attach some static piece of extra information to the message. An attacker could just copy that information and replicate it to forge your signature on another, potentially malicious document. In other words, a signature should only work for the message it was used to sign. The technique we’ll implement was originally proposed by Taher Elgamal, and is called the ElGamal signature algorithm. We’re going to look at a special case of it.

So Alice wants to send a message $ m$ with some extra information that is unique to the message and that can be used to verify that it was sent by Alice. She picks an elliptic curve $ E$ over $ \mathbb{F}_q$ in such a way that the number of points on $ E$ is $ br$, where $ b$ is a small integer and $ r$ is a large prime.

Then, as in Diffie-Hellman, she picks a base point $ Q$ that has order $ r$ and a secret integer $ s$ (which is permanent), and computes $ P = sQ$. Alice publishes everything except $ s$:

Public information: $\mathbb{F}_q, E, b, r, Q, P$

Let Alice’s message $ m$ be represented as an integer at most $ r$ (there are a few ways to get around this if your message is too long). Now to sign $ m$ Alice picks a message specific $ k < r$ and computes what I’ll call the auxiliary point $ A = kQ$. Let $ A = (x, y)$. Alice then computes the signature $ g = k^{-1}(m + s x) \mod r$. The signed message is then $ (m, A, g)$, which Alice can safely send to Bob.

Before we see how Bob verifies the message, notice that the signature integer involves everything: Alice’s secret key, the message-specific secret integer $ k$, and most importantly the message. Remember that this is crucial: we want the signature to work only for the message that it was used to sign. If the same $ k$ is used for multiple messages then the attacker can find out your secret key! (And this has happened in practice; see the end of the post.)

So Bob receives $ (m, A, g)$, and also has access to all of the public information listed above. Bob authenticates the message by computing the auxiliary point via a different route. First, he computes $ c = g^{-1} m \mod r$ and $ d = g^{-1}x \mod r$, and then $ A’ = cQ + dP$. If the message was signed by Alice then $ A’ = A$, since we can just write out the definition of everything:

\[ \begin{aligned} A' = cQ + dP &= g^{-1}mQ + g^{-1}xP \\ &= g^{-1}mQ + g^{-1}xsQ \\ &= g^{-1}(m + xs)Q \\ &= k(m + sx)^{-1}(m+sx)Q \\ &= kQ \\ &= A \end{aligned} \]Now to analyze the security. The attacker wants to be able to take any message $ m’$ and produce a signature $ A’, g’$ that will pass validation with Alice’s public information. If the attacker knew how to solve the discrete logarithm problem efficiently this would be trivial: compute $ s$ and then just sign like Alice does. Without that power there are still a few options. If the attacker can figure out the message-specific integer $ k$, then she can compute Alice’s secret key $ s$ as follows.

Given $ g = k^{-1}(m + sx) \mod r$, compute $ kg \equiv (m + sx) \mod r$. Compute $ d = gcd(x, r)$, and you know that this congruence has only $ d$ possible solutions modulo $ r$. Since $ s$ is less than $ r$, the attacker can just try all options until they find $ P = sQ$. So that’s bad, but in a properly implemented signature algorithm finding $ k$ is equivalently hard to solving the discrete logarithm problem, so we can assume we’re relatively safe from that.

On the other hand one could imagine being able to conjure the pieces of the signature $ A’, g’$ by some method that doesn’t involve directly finding Alice’s secret key. Indeed, this problem is less well-studied than the Diffie-Hellman problem, but most cryptographers believe it’s just as hard. For more information, this paper surveys the known attacks against this signature algorithm, including a successful attack for fields of characteristic two.

Signature Implementation

We can go ahead and implement the signature algorithm once we’ve picked a suitable elliptic curve. For the purpose of demonstration we’ll use a small curve, $ E: y^2 = x^3 + 3x + 181$ over $ F = \mathbb{Z}/1061$, whose number of points happens to have the a suitable prime factorization ($ 1047 = 3 \cdot 349$). If you’re interested in counting the number of points on an elliptic curve, there are many theorems and efficient algorithms to do this, and if you’ve been reading this whole series something then an algorithm based on the Baby-Step Giant-Step idea would be easy to implement. For the sake of brevity, we leave it as an exercise to the reader.

Note that the code we present is based on the elliptic curve and finite field code we’re been implementing as part of this series. All of the code used in this post is available on this blog’s Github page.

The basepoint we’ll pick has to have order 349, and $ E$ has plenty of candidates. We’ll use $ (2, 81)$, and we’ll randomly generate a secret key that’s less than $ 349$ (eight bits will do). So our setup looks like this:

if __name__ == "__main__":

F = FiniteField(1061, 1)

# y^2 = x^3 + 3x + 181

curve = EllipticCurve(a=F(3), b=F(181))

basePoint = Point(curve, F(2), F(81))

basePointOrder = 349

secretKey = generateSecretKey(8)

publicKey = secretKey * basePoint

Then so sign a message we generate a random key, construct the auxiliary point and the signature, and return:

def sign(message, basePoint, basePointOrder, secretKey):

modR = FiniteField(basePointOrder, 1)

oneTimeSecret = generateSecretKey(len(bin(basePointOrder)) - 3) # numbits(order) - 1

auxiliaryPoint = oneTimeSecret * basePoint

signature = modR(oneTimeSecret).inverse() *

(modR(message) + modR(secretKey) * modR(auxiliaryPoint[0]))

return (message, auxiliaryPoint, signature)

So far so good. Note that we generate the message-specific $ k$ at random, and this implies we need a high-quality source of randomness (what’s called a cryptographically-secure pseudorandom number generator). In absence of that there are proposed deterministic methods for doing it. See this draft proposal of Thomas Pornin, and this paper of Daniel Bernstein for another.

Now to authenticate, we follow the procedure from earlier.

def authentic(signedMessage, basePoint, basePointOrder, publicKey):

modR = FiniteField(basePointOrder, 1)

(message, auxiliary, signature) = signedMessage

sigInverse = modR(signature).inverse() # sig can be an int or a modR already

c, d = sigInverse * modR(message), sigInverse * modR(auxiliary[0])

auxiliaryChecker = int(c) * basePoint + int(d) * publicKey

return auxiliaryChecker == auxiliary

Continuing with our example, we pick a message represented as an integer smaller than $ r$, sign it, and validate it.

>>> message = 123

>>> signedMessage = sign(message, basePoint, basePointOrder, secretKey)

>>> signedMessage

(123, (220 (mod 1061), 234 (mod 1061)), 88 (mod 349))

>>> authentic(signedMessage, basePoint, basePointOrder, publicKey)

True

So there we have it, a nice implementation of the digital signature algorithm.

When Digital Signatures Fail

As we mentioned, it’s extremely important to avoid using the same $ k$ for two different messages. If you do, then you’ll get two signed messages $ (m_1, A_1, g_1), (m_2, A_2, g_2)$, but by definition the two $ g$’s have a ton of information in common! An attacker can recognize this immediately because $ A_1 = A_2$, and figure out the secret key $ s$ as follows. First write

\[ g_1 – g_2 \equiv k^{-1}(m_1 + sx) – k^{-1}(m_2 + sx) \equiv k^{-1}(m_1 – m_2) \mod r \]Now we have something of the form $ \text{known}_1 \equiv (k^{-1}) \text{known}_2 \mod r$, and similarly to the attack described earlier we can try all possibilities until we find a number that satisfies $ A = kQ$. Then once we have $ k$ we have already seen how to find $ s$. Indeed, it would be a good exercise for the reader to implement this attack.

The attack we just described it not an idle threat. Indeed, the Sony corporation, producers of the popular Playstation video game console, made this mistake in signing software for Playstation 3. A digital signature algorithm makes sense to validate software, because Sony wants to ensure that only Sony has the power to publish games. So Sony developers act as one party signing the data on a disc, and the console will only play a game with a valid signature. Note that the asymmetric setup is necessary because if the console had shared a secret with Sony (say, stored as plaintext within the hardware of the console), anyone with physical access to the machine could discover it.

Now here come the cringing part. Sony made the mistake of using the same $ k$ to sign every game! Their mistake was discovered in 2010 and made public at a cryptography conference. This video of the humorous talk includes a description of the variant Sony used and the attacker describe how the mistake should have been corrected. Without a firmware update (I believe Sony’s public key information was stored locally so that one could authenticate games without an internet connection), anyone could sign a piece of software and create games that are indistinguishable from something produced by Sony. That includes malicious content that, say, installs software that sends credit card information to the attacker.

So here we have a tidy story: a widely used cryptosystem with a scare story of what will go wrong when you misuse it. In the future of this series, we’ll look at other things you can do with elliptic curves, including factoring integers and testing for primality. We’ll also see some normal forms of elliptic curves that are used in place of the Weierstrass normal form for various reasons.

Until next time!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.