A while back Peter Norvig posted a wonderful pair of articles about regex golf. The idea behind regex golf is to come up with the shortest possible regular expression that matches one given list of strings, but not the other.

“Regex Golf,” by Randall Munroe.

In the first article, Norvig runs a basic algorithm to recreate and improve the results from the comic, and in the second he beefs it up with some improved search heuristics. My favorite part about this topic is that regex golf can be phrased in terms of a problem called set cover. I noticed this when reading the comic, and was delighted to see Norvig use that as the basis of his algorithm.

The set cover problem shows up in other places, too. If you have a database of items labeled by users, and you want to find the smallest set of labels to display that covers every item in the database, you’re doing set cover. I hear there are applications in biochemistry and biology but haven’t seen them myself.

If you know what a set is (just think of the “set” or “hash set” type from your favorite programming language), then set cover has a simple definition.

Definition (The Set Cover Problem): You are given a finite set $ U$ called a “universe” and sets $ S_1, \dots, S_n$ each of which is a subset of $ U$. You choose some of the $ S_i$ to ensure that every $ x \in U$ is in one of your chosen sets, and you want to minimize the number of $ S_i$ you picked.

It’s called a “cover” because the sets you pick “cover” every element of $ U$. Let’s do a simple. Let $ U = \{ 1,2,3,4,5 \}$ and

$$S_1 = \{ 1,3,4 \}, S_2 = \{ 2,3,5 \}, S_3 = \{ 1,4,5 \}, S_4 = \{ 2,4 \}$$Then the smallest possible number of sets you can pick is 2, and you can achieve this by picking both $ S_1, S_2$ or both $ S_2, S_3$. The connection to regex golf is that you pick $ U$ to be the set of strings you want to match, and you pick a set of regexes that match some of the strings in $ U$ but none of the strings you want to avoid matching (I’ll call them $ V$). If $ w$ is such a regex, then you can form the set $ S_w$ of strings that $ w$ matches. Then if you find a small set cover with the strings $ w_1, \dots, w_t$, then you can “or” them together to get a single regex $ w_1 \mid w_2 \mid \dots \mid w_t$ that matches all of $ U$ but none of $ V$.

Set cover is what’s called NP-hard, and one implication is that we shouldn’t hope to find an efficient algorithm that will always give you the shortest regex for every regex golf problem. But despite this, there are approximation algorithms for set cover. What I mean by this is that there is a regex-golf algorithm $ A$ that outputs a subset of the regexes matching all of $ U$, and the number of regexes it outputs is such-and-such close to the minimum possible number. We’ll make “such-and-such” more formal later in the post.

What made me sad was that Norvig didn’t go any deeper than saying, “We can try to approximate set cover, and the greedy algorithm is pretty good.” It’s true, but the ideas are richer than that! Set cover is a simple example to showcase interesting techniques from theoretical computer science. And perhaps ironically, in Norvig’s second post a header promised the article would discuss the theory of set cover, but I didn’t see any of what I think of as theory. Instead he partially analyzes the structure of the regex golf instances he cares about. This is useful, but not really theoretical in any way unless he can say something universal about those instances.

I don’t mean to bash Norvig. His articles were great! And in-depth theory was way beyond scope. So this post is just my opportunity to fill in some theory gaps. We’ll do three things:

- Show formally that set cover is NP-hard.

- Prove the approximation guarantee of the greedy algorithm.

- Show another (very different) approximation algorithm based on linear programming.

Along the way I’ll argue that by knowing (or at least seeing) the details of these proofs, one can get a better sense of what features to look for in the set cover instance you’re trying to solve. We’ll also see how set cover depicts the broader themes of theoretical computer science.

NP-hardness

The first thing we should do is show that set cover is NP-hard. Intuitively what this means is that we can take some hard problem $ P$ and encode instances of $ P$ inside set cover problems. This idea is called a reduction, because solving problem $ P$ will “reduce” to solving set cover, and the method we use to encode instance of $ P$ as set cover problems will have a small amount of overhead. This is one way to say that set cover is “at least as hard as” $ P$.

The hard problem we’ll reduce to set cover is called 3-satisfiability (3-SAT). In 3-SAT, the input is a formula whose variables are either true or false, and the formula is expressed as an OR of a bunch of clauses, each of which is an AND of three variables (or their negations). This is called 3-CNF form. A simple example:

$$(x \vee y \vee \neg z) \wedge (\neg x \vee w \vee y) \wedge (z \vee x \vee \neg w)$$The goal of the algorithm is to decide whether there is an assignment to the variables which makes the formula true. 3-SAT is one of the most fundamental problems we believe to be hard and, roughly speaking, by reducing it to set cover we include set cover in a class called NP-complete, and if any one of these problems can be solved efficiently, then they all can (this is the famous P versus NP problem, and an efficient algorithm would imply P equals NP).

So a reduction would consist of the following: you give me a formula $ \varphi$ in 3-CNF form, and I have to produce (in a way that depends on $ \varphi$!) a universe $ U$ and a choice of subsets $ S_i \subset U$ in such a way that

$ \varphi$ has a true assignment of variables if and only if the corresponding set cover problem has a cover using $ k$ sets.

In other words, I’m going to design a function $ f$ from 3-SAT instances to set cover instances, such that $ x$ is satisfiable if and only if $ f(x)$ has a set cover with $ k$ sets.

Why do I say it only for $ k$ sets? Well, if you can always answer this question then I claim you can find the minimum size of a set cover needed by doing a binary search for the smallest value of $ k$. So finding the minimum size of a set cover reduces to the problem of telling if theres a set cover of size $ k$.

Now let’s do the reduction from 3-SAT to set cover.

If you give me $ \varphi = C_1 \wedge C_2 \wedge \dots \wedge C_m$ where each $ C_i$ is a clause and the variables are denoted $ x_1, \dots, x_n$, then I will choose as my universe $ U$ to be the set of all the clauses and indices of the variables (these are all just formal symbols). i.e.

$$U = \{ C_1, C_2, \dots, C_m, 1, 2, \dots, n \}$$The first part of $ U$ will ensure I make all the clauses true, and the last part will ensure I don’t pick a variable to be both true and false at the same time.

To show how this works I have to pick my subsets. For each variable $ x_i$, I’ll make two sets, one called $ S_{x_i}$ and one called $ S_{\neg x_i}$. They will both contain $ i$ in addition to the clauses which they make true when the corresponding literal is true (by literal I just mean the variable or its negation). For example, if $ C_j$ uses the literal $ \neg x_7$, then $ S_{\neg x_7}$ will contain $ C_j$ but $ S_{x_7}$ will not. Finally, I’ll set $ k = n$, the number of variables.

Now to prove this reduction works I have to prove two things: if my starting formula has a satisfying assignment I have to show the set cover problem has a cover of size $ k$. Indeed, take the sets $ S_{y}$ for all literals $ y$ that are set to true in a satisfying assignment. There can be at most $ n$ true literals since half are true and half are false, so there will be at most $ n$ sets, and these sets clearly cover all of $ U$ because every literal has to be satisfied by some literal or else the formula isn’t true.

The reverse direction is similar: if I have a set cover of size $ n$, I need to use it to come up with a satisfying truth assignment for the original formula. But indeed, the sets that get chosen can’t include both a $ S_{x_i}$ and its negation set $ S_{\neg x_i}$, because there are $ n$ of the elements $ \{1, 2, \dots, n \} \subset U$, and each $ i$ is only in the two $ S_{x_i}, S_{\neg x_i}$. Just by counting if I cover all the indices $ i$, I already account for $ n$ sets! And finally, since I have covered all the clauses, the literals corresponding to the sets I chose give exactly a satisfying assignment.

Whew! So set cover is NP-hard because I encoded this logic problem 3-SAT within its rules. If we think 3-SAT is hard (and we do) then set cover must also be hard. So if we can’t hope to solve it exactly we should try to approximate the best solution.

The greedy approach

The method that Norvig uses in attacking the meta-regex golf problem is the greedy algorithm. The greedy algorithm is exactly what you’d expect: you maintain a list $ L$ of the subsets you’ve picked so far, and at each step you pick the set $ S_i$ that maximizes the number of new elements of $ U$ that aren’t already covered by the sets in $ L$. In python pseudocode:

def greedySetCover(universe, sets):

chosenSets = set()

leftToCover = universe.copy()

unchosenSets = sets

covered = lambda s: leftToCover & s

while universe != 0:

if len(chosenSets) == len(sets):

raise Exception("No set cover possible")

nextSet = max(unchosenSets, key=lambda s: len(covered(s)))

unchosenSets.remove(nextSet)

chosenSets.add(nextSet)

leftToCover -= nextSet

return chosenSets

This is what theory has to say about the greedy algorithm:

Theorem: If it is possible to cover $ U$ by the sets in $ F = \{ S_1, \dots, S_n \}$, then the greedy algorithm always produces a cover that at worst has size $ O(\log(n)) \textup{OPT}$, where $ \textup{OPT}$ is the size of the smallest cover. Moreover, this is asymptotically the best any algorithm can do.

One simple fact we need from calculus is that the following sum is asymptotically the same as $ \log(n)$:

$$H(n) = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \dots + \frac{1}{n} = \log(n) + O(1)$$Proof. [adapted from Wan] Let’s say the greedy algorithm picks sets $ T_1, T_2, \dots, T_k$ in that order. We’ll set up a little value system for the elements of $ U$. Specifically, the value of each $ T_i$ is 1, and in step $ i$ we evenly distribute this unit value across all newly covered elements of $ T_i$. So for $ T_1$ each covered element gets value $ 1/|T_1|$, and if $ T_2$ covers four new elements, each gets a value of 1/4. One can think of this “value” as a price, or energy, or unit mass, or whatever. It’s just an accounting system (albeit a clever one) we use to make some inequalities clear later.

In general call the value $ v_x$ of element $ x \in U$ the value assigned to $ x$ at the step where it’s first covered. In particular, the number of sets chosen by the greedy algorithm $ k$ is just $ \sum_{x \in U} v_x$. We’re just bunching back together the unit value we distributed for each step of the algorithm.

Now we want to compare the sets chosen by greedy to the optimal choice. Call a smallest set cover $ C_{\textup{OPT}}$. Let’s stare at the following inequality.

$$\sum_{x \in U} v_x \leq \sum_{S \in C_{\textup{OPT}}} \sum_{x \in S} v_x$$It’s true because each $ x$ counts for a $ v_x$ at most once in the left hand side, and in the right hand side the sets in $ C_{\textup{OPT}}$ must hit each $ x$ at least once but may hit some $ x$ more than once. Also remember the left hand side is equal to $ k$.

Now we want to show that the inner sum on the right hand side, $ \sum_{x \in S} v_x$, is at most $ H(|S|)$. This will in fact prove the entire theorem: because each set $ S_i$ has size at most $ n$, the inequality above will turn into

$$k \leq |C_{\textup{OPT}}| H(|S|) \leq |C_{\textup{OPT}}| H(n)$$And so $ k \leq \textup{OPT} \cdot O(\log(n))$, which is the statement of the theorem.

So we want to show that $ \sum_{x \in S} v_x \leq H(|S|)$. For each $ j$ define $ \delta_j(S)$ to be the number of elements in $ S$ not covered in $ T_1, \cup \dots \cup T_j$. Notice that $ \delta_{j-1}(S) – \delta_{j}(S)$ is the number of elements of $ S$ that are covered for the first time in step $ j$. If we call $ t_S$ the smallest integer $ j$ for which $ \delta_j(S) = 0$, we can count up the differences up to step $ t_S$, we get

$$\sum_{x \in S} v_x = \sum_{i=1}^{t_S} (\delta_{i-1}(S) – \delta_i(S)) \cdot \frac{1}{T_i – (T_1 \cup \dots \cup T_{i-1})}$$The rightmost term is just the cost assigned to the relevant elements at step $ i$. Moreover, because $ T_i$ covers more new elements than $ S$ (by definition of the greedy algorithm), the fraction above is at most $ 1/\delta_{i-1}(S)$. The end is near. For brevity I’ll drop the $ (S)$ from $ \delta_j(S)$.

$$\begin{aligned} \sum_{x \in S} v_x & \leq \sum_{i=1}^{t_S} (\delta_{i-1} – \delta_i) \frac{1}{\delta_{i-1}} \\\ & \leq \sum_{i=1}^{t_S} (\frac{1}{1 + \delta_i} + \frac{1}{2+\delta_i} \dots + \frac{1}{\delta_{i-1}}) \\\ & = \sum_{i=1}^{t_S} H(\delta_{i-1}) – H(\delta_i) \\\ &= H(\delta_0) – H(\delta_{t_S}) = H(|S|) \end{aligned}$$And that proves the claim.

$$\square$$I have three postscripts to this proof:

- This is basically the exact worst-case approximation that the greedy algorithm achieves. In fact, Petr Slavik proved in 1996 that the greedy gives you a set of size exactly $ (\log n – \log \log n + O(1)) \textup{OPT}$ in the worst case.

- This is also the best approximation that any set cover algorithm can achieve, provided that P is not NP. This result was basically known in 1994, but it wasn’t until 2013 and the use of some very sophisticated tools that the best possible bound was found with the smallest assumptions.

- In the proof we used that $ |S| \leq n$ to bound things, but if we knew that our sets $ S_i$ (i.e. subsets matched by a regex) had sizes bounded by, say, $ B$, the same proof would show that the approximation factor is $ \log(B)$ instead of $ \log n$. However, in order for that to be useful you need $ B$ to be a constant, or at least to grow more slowly than any polynomial in $ n$, since e.g. $ \log(n^{0.1}) = 0.1 \log n$. In fact, taking a second look at Norvig’s meta regex golf problem, some of his instances had this property! Which means the greedy algorithm gives a much better approximation ratio for certain meta regex golf problems than it does for the worst case general problem. This is one instance where knowing the proof of a theorem helps us understand how to specialize it to our interests.

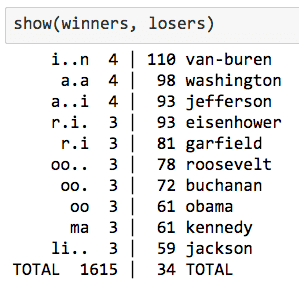

norvig-table

The linear programming approach

So we just said that you can’t possibly do better than the greedy algorithm for approximating set cover. There must be nothing left to say, job well done, right? Wrong! Our second analysis, based on linear programming, shows that instances with special features can have better approximation results.

In particular, if we’re guaranteed that each element $ x \in U$ occurs in at most $ B$ of the sets $ S_i$, then the linear programming approach will give a $ B$-approximation, i.e. a cover whose size is at worst larger than OPT by a multiplicative factor of $ B$. In the case that $ B$ is constant, we can beat our earlier greedy algorithm.

The technique is now a classic one in optimization, called LP-relaxation (LP stands for linear programming). The idea is simple. Most optimization problems can be written as integer linear programs, that is there you have $ n$ variables $ x_1, \dots, x_n \in \{ 0, 1 \}$ and you want to maximize (or minimize) a linear function of the $ x_i$ subject to some linear constraints. The thing you’re trying to optimize is called the objective. While in general solving integer linear programs is NP-hard, we can relax the “integer” requirement to $ 0 \leq x_i \leq 1$, or something similar. The resulting linear program, called the relaxed program, can be solved efficiently using the simplex algorithm or another more complicated method.

The output of solving the relaxed program is an assignment of real numbers for the $ x_i$ that optimizes the objective function. A key fact is that the solution to the relaxed linear program will be at least as good as the solution to the original integer program, because the optimal solution to the integer program is a valid candidate for the optimal solution to the linear program. Then the idea is that if we use some clever scheme to round the $ x_i$ to integers, we can measure how much this degrades the objective and prove that it doesn’t degrade too much when compared to the optimum of the relaxed program, which means it doesn’t degrade too much when compared to the optimum of the integer program as well.

If this sounds wishy washy and vague don’t worry, we’re about to make it super concrete for set cover.

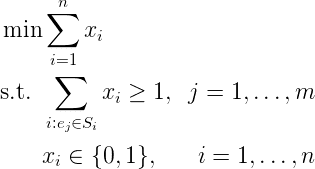

We’ll make a binary variable $ x_i$ for each set $ S_i$ in the input, and $ x_i = 1$ if and only if we include it in our proposed cover. Then the objective function we want to minimize is $ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i$. If we call our elements $ X = \{ e_1, \dots, e_m \}$, then we need to write down a linear constraint that says each element $ e_j$ is hit by at least one set in the proposed cover. These constraints have to depend on the sets $ S_i$, but that’s not a problem. One good constraint for element $ e_j$ is

$$\sum_{i : e_j \in S_i} x_i \geq 1$$In words, the only way that an $ e_j$ will not be covered is if all the sets containing it have their $ x_i = 0$. And we need one of these constraints for each $ j$. Putting it together, the integer linear program is

The integer program for set cover.

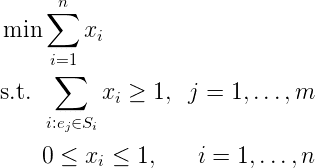

Once we understand this formulation of set cover, the relaxation is trivial. We just replace the last constraint with inequalities.

setcoverlp

For a given candidate assignment $ x$ to the $ x_i$, call $ Z(x)$ the objective value (in this case $ \sum_i x_i$). Now we can be more concrete about the guarantees of this relaxation method. Let $ \textup{OPT}_{\textup{IP}}$ be the optimal value of the integer program and $ x_{\textup{IP}}$ a corresponding assignment to $ x_i$ achieving the optimum. Likewise let $ \textup{OPT}_{\textup{LP}}, x_{\textup{LP}}$ be the optimal things for the linear relaxation. We will prove:

Theorem: There is a deterministic algorithm that rounds $ x_{\textup{LP}}$ to integer values $ x$ so that the objective value $ Z(x) \leq B \textup{OPT}_{\textup{IP}}$, where $ B$ is the maximum number of sets that any element $ e_j$ occurs in. So this gives a $ B$-approximation of set cover.

Proof. Let $ B$ be as described in the theorem, and call $ y = x_{\textup{LP}}$ to make the indexing notation easier. The rounding algorithm is to set $ x_i = 1$ if $ y_i \geq 1/B$ and zero otherwise.

To prove the theorem we need to show two things hold about this new candidate solution $ x$:

- The choice of all $ S_i$ for which $ x_i = 1$ covers every element.

- The number of sets chosen (i.e. $ Z(x)$) is at most $ B$ times more than $ \textup{OPT}_{\textup{LP}}$.

Since $ \textup{OPT}_{\textup{LP}} \leq \textup{OPT}_{\textup{IP}}$, so if we can prove number 2 we get $ Z(x) \leq B \textup{OPT}_{\textup{LP}} \leq B \textup{OPT}_{\textup{IP}}$, which is the theorem.

So let’s prove 1. Fix any $ j$ and we’ll show that element $ e_j$ is covered by some set in the rounded solution. Call $ B_j$ the number of times element $ e_j$ occurs in the input sets. By definition $ B_j \leq B$, so $ 1/B_j \geq 1/B$. Recall $ y$ was the optimal solution to the relaxed linear program, and so it must be the case that the linear constraint for each $ e_j$ is satisfied: $ \sum_{i : e_j \in S_i} x_i \geq 1$. We know that there are $ B_j$ terms and they sums to at least 1, so not all terms can be smaller than $ 1/B_j$ (otherwise they’d sum to something less than 1). In other words, some variable $ x_i$ in the sum is at least $ 1/B_j \geq 1/B$, and so $ x_i$ is set to 1 in the rounded solution, corresponding to a set $ S_i$ that contains $ e_j$. This finishes the proof of 1.

Now let’s prove 2. For each $ j$, we know that for each $ x_i = 1$, the corresponding variable $ y_i \geq 1/B$. In particular $ 1 \leq y_i B$. Now we can simply bound the sum.

$$\begin{aligned} Z(x) = \sum_i x_i &\leq \sum_i x_i (B y_i) \\\ &\leq B \sum_{i} y_i \\\ &= B \cdot \textup{OPT}_{\textup{LP}} \end{aligned}$$The second inequality is true because some of the $ x_i$ are zero, but we can ignore them when we upper bound and just include all the $ y_i$. This proves part 2 and the theorem.

$$\square$$I’ve got some more postscripts to this proof:

- The proof works equally well when the sets are weighted, i.e. your cost for picking a set is not 1 for every set but depends on some arbitrarily given constants $ w_i \geq 0$.

- We gave a deterministic algorithm rounding $ y$ to $ x$, but one can get the same result (with high probability) using a randomized algorithm. The idea is to flip a coin with bias $ y_i$ roughly $ \log(n)$ times and set $ x_i = 1$ if and only if the coin lands heads at least once. The guarantee is no better than what we proved, but for some other problems randomness can help you get approximations where we don’t know of any deterministic algorithms to get the same guarantees. I can’t think of any off the top of my head, but I’m pretty sure they’re out there.

- For step 1 we showed that at least one term in the inequality for $ e_j$ would be rounded up to 1, and this guaranteed we covered all the elements. A natural question is: why not also round up at most one term of each of these inequalities? It might be that in the worst case you don’t get a better guarantee, but it would be a quick extra heuristic you could use to post-process a rounded solution.

- Solving linear programs is slow. There are faster methods based on so-called “primal-dual” methods that use information about the dual of the linear program to construct a solution to the problem. Goemans and Williamson have a nice self-contained chapter on their website about this with a ton of applications.

Additional Reading

Williamson and Shmoys have a large textbook called The Design of Approximation Algorithms. One problem is that this field is like a big heap of unrelated techniques, so it’s not like the book will build up some neat theoretical foundation that works for every problem. Rather, it’s messy and there are lots of details, but there are definitely diamonds in the rough, such as the problem of (and algorithms for) coloring 3-colorable graphs with “approximately 3” colors, and the infamous unique games conjecture.

I wrote a post a while back giving conditions which, if a problem satisfies those conditions, the greedy algorithm will give a constant-factor approximation. This is much better than the worst case $ \log(n)$-approximation we saw in this post. Moreover, I also wrote a post about matroids, which is a characterization of problems where the greedy algorithm is actually optimal.

Set cover is one of the main tools that IBM’s AntiVirus software uses to detect viruses. Similarly to the regex golf problem, they find a set of strings that occurs source code in some viruses but not (usually) in good programs. Then they look for a small set of strings that covers all the viruses, and their virus scan just has to search binaries for those strings. Hopefully the size of your set cover is really small compared to the number of viruses you want to protect against. I can’t find a reference that details this, but that is understandable because it is proprietary software.

Until next time!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.