I’m just going to jump right into the definitions and rigor, so if you haven’t read the previous post motivating the singular value decomposition, go back and do that first. This post will be theorem, proof, algorithm, data. The data set we test on is a thousand-story CNN news data set. All of the data, code, and examples used in this post is in a github repository, as usual.

We start with the best-approximating $ k$-dimensional linear subspace.

Definition: Let $ X = \{ x_1, \dots, x_m \}$ be a set of $ m$ points in $ \mathbb{R}^n$. The best approximating $ k$-dimensional linear subspace of $ X$ is the $ k$-dimensional linear subspace $ V \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ which minimizes the sum of the squared distances from the points in $ X$ to $ V$.

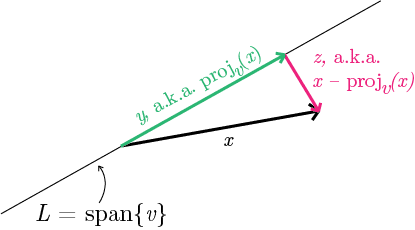

Let me clarify what I mean by minimizing the sum of squared distances. First we’ll start with the simple case: we have a vector $ x \in X$, and a candidate line $ L$ (a 1-dimensional subspace) that is the span of a unit vector $ v$. The squared distance from $ x$ to the line spanned by $ v$ is the squared length of $ x$ minus the squared length of the projection of $ x$ onto $ v$. Here’s a picture.

vectormax

I’m saying that the pink vector $ z$ in the picture is the difference of the black and green vectors $ x-y$, and that the “distance” from $ x$ to $ v$ is the length of the pink vector. The reason is just the Pythagorean theorem: the vector $ x$ is the hypotenuse of a right triangle whose other two sides are the projected vector $ y$ and the difference vector $ z$.

Let’s throw down some notation. I’ll call $ \textup{proj}_v: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^n$ the linear map that takes as input a vector $ x$ and produces as output the projection of $ x$ onto $ v$. In fact we have a brief formula for this when $ v$ is a unit vector. If we call $ x \cdot v$ the usual dot product, then $ \textup{proj}_v(x) = (x \cdot v)v$. That’s $ v$ scaled by the inner product of $ x$ and $ v$. In the picture above, since the line $ L$ is the span of the vector $ v$, that means that $ y = \textup{proj}_v(x)$ and $ z = x -\textup{proj}_v(x) = x-y$.

The dot-product formula is useful for us because it allows us to compute the squared length of the projection by taking a dot product $ |x \cdot v|^2$. So then a formula for the distance of $ x$ from the line spanned by the unit vector $ v$ is

$$\displaystyle (\textup{dist}_v(x))^2 = \left ( \sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2 \right ) – |x \cdot v|^2$$This formula is just a restatement of the Pythagorean theorem for perpendicular vectors.

$$\displaystyle \sum_{i} x_i^2 = (\textup{proj}_v(x))^2 + (\textup{dist}_v(x))^2$$In particular, the difference vector we originally called $ z$ has squared length $ \textup{dist}_v(x)^2$. The vector $ y$, which is perpendicular to $ z$ and is also the projection of $ x$ onto $ L$, it’s squared length is $ (\textup{proj}_v(x))^2$. And the Pythagorean theorem tells us that summing those two squared lengths gives you the squared length of the hypotenuse $ x$.

If we were trying to find the best approximating 1-dimensional subspace for a set of data points $ X$, then we’d want to minimize the sum of the squared distances for every point $ x \in X$. Namely, we want the $ v$ that solves $ \min_{|v|=1} \sum_{x \in X} (\textup{dist}_v(x))^2$.

With some slight algebra we can make our life easier. The short version: minimizing the sum of squared distances is the same thing as maximizing the sum of squared lengths of the projections. The longer version: let’s go back to a single point $ x$ and the line spanned by $ v$. The Pythagorean theorem told us that

$$\displaystyle \sum_{i} x_i^2 = (\textup{proj}_v(x))^2 + (\textup{dist}_v(x))^2$$The squared length of $ x$ is constant. It’s an input to the algorithm and it doesn’t change through a run of the algorithm. So we get the squared distance by subtracting $ (\textup{proj}_v(x))^2$ from a constant number,

$$\displaystyle \sum_{i} x_i^2 – (\textup{proj}_v(x))^2 = (\textup{dist}_v(x))^2$$which means if we want to minimize the squared distance, we can instead maximize the squared projection. Maximizing the subtracted thing minimizes the whole expression.

It works the same way if you’re summing over all the data points in $ X$. In fact, we can say it much more compactly this way. If the rows of $ A$ are your data points, then $ Av$ contains as each entry the (signed) dot products $ x_i \cdot v$. And the squared norm of this vector, $ |Av|^2$, is exactly the sum of the squared lengths of the projections of the data onto the line spanned by $ v$. The last thing is that maximizing a square is the same as maximizing its square root, so we can switch freely between saying our objective is to find the unit vector $ v$ that maximizes $ |Av|$ and that which maximizes $ |Av|^2$.

At this point you should be thinking,

Great, we have written down an optimization problem: $ \max_{v : |v|=1} |Av|$. If we could solve this, we’d have the best 1-dimensional linear approximation to the data contained in the rows of $ A$. But (1) how do we solve that problem? And (2) you promised a $ k$-dimensional approximating subspace. I feel betrayed! Swindled! Bamboozled!

Here’s the fantastic thing. We can solve the 1-dimensional optimization problem efficiently (we’ll do it later in this post), and (2) is answered by the following theorem.

The SVD Theorem: Computing the best $ k$-dimensional subspace reduces to $ k$ applications of the one-dimensional problem.

We will prove this after we introduce the terms “singular value” and “singular vector.”

Singular values and vectors

As I just said, we can get the best $ k$-dimensional approximating linear subspace by solving the one-dimensional maximization problem $ k$ times. The singular vectors of $ A$ are defined recursively as the solutions to these sub-problems. That is, I’ll call $ v_1$ the first singular vector of $ A$, and it is:

$$\displaystyle v_1 = \arg \max_{v, |v|=1} |Av|$$And the corresponding first singular value, denoted $ \sigma_1(A)$, is the maximal value of the optimization objective, i.e. $ |Av_1|$. (I will use this term frequently, that $ |Av|$ is the “objective” of the optimization problem.) Informally speaking, $ (\sigma_1(A))^2$ represents how much of the data was captured by the first singular vector. Meaning, how close the vectors are to lying on the line spanned by $ v_1$. Larger values imply the approximation is better. In fact, if all the data points lie on a line, then $ (\sigma_1(A))^2$ is the sum of the squared norms of the rows of $ A$.

Now here is where we see the reduction from the $ k$-dimensional case to the 1-dimensional case. To find the best 2-dimensional subspace, you first find the best one-dimensional subspace (spanned by $ v_1$), and then find the best 1-dimensional subspace, but only considering those subspaces that are the spans of unit vectors perpendicular to $ v_1$. The notation for “vectors $ v$ perpendicular to $ v_1$” is $ v \perp v_1$. Restating, the second singular vector $ v _2$ is defined as

$$\displaystyle v_2 = \arg \max_{v \perp v_1, |v| = 1} |Av|$$And the SVD theorem implies the subspace spanned by $ \{ v_1, v_2 \}$ is the best 2-dimensional linear approximation to the data. Likewise $ \sigma_2(A) = |Av_2|$ is the second singular value. Its squared magnitude tells us how much of the data that was not “captured” by $ v_1$ is captured by $ v_2$. Again, if the data lies in a 2-dimensional subspace, then the span of $ \{ v_1, v_2 \}$ will be that subspace.

We can continue this process. Recursively define $ v_k$, the $ k$-th singular vector, to be the vector which maximizes $ |Av|$, when $ v$ is considered only among the unit vectors which are perpendicular to $ \textup{span} \{ v_1, \dots, v_{k-1} \}$. The corresponding singular value $ \sigma_k(A)$ is the value of the optimization problem.

As a side note, because of the way we defined the singular values as the objective values of “nested” optimization problems, the singular values are decreasing, $ \sigma_1(A) \geq \sigma_2(A) \geq \dots \geq \sigma_n(A) \geq 0$. This is obvious: you only pick $ v_2$ in the second optimization problem because you already picked $ v_1$ which gave a bigger singular value, so $ v_2$’s objective can’t be bigger.

If you keep doing this, one of two things happen. Either you reach $ v_n$ and since the domain is $ n$-dimensional there are no remaining vectors to choose from, the $ v_i$ are an orthonormal basis of $ \mathbb{R}^n$. This means that the data in $ A$ contains a full-rank submatrix. The data does not lie in any smaller-dimensional subspace. This is what you’d expect from real data.

Alternatively, you could get to a stage $ v_k$ with $ k < n$ and when you try to solve the optimization problem you find that every perpendicular $ v$ has $ Av = 0$. In this case, the data actually does lie in a $ k$-dimensional subspace, and the first-through-$ k$-th singular vectors you computed span this subspace.

Let’s do a quick sanity check: how do we know that the singular vectors $ v_i$ form a basis? Well formally they only span a basis of the row space of $ A$, i.e. a basis of the subspace spanned by the data contained in the rows of $ A$. But either way the point is that each $ v_{i+1}$ spans a new dimension from the previous $ v_1, \dots, v_i$ because we’re choosing $ v_{i+1}$ to be orthogonal to all the previous $ v_i$. So the answer to our sanity check is “by construction.”

Back to the singular vectors, the discussion from the last post tells us intuitively that the data is probably never in a small subspace. You never expect the process of finding singular vectors to stop before step $ n$, and if it does you take a step back and ask if something deeper is going on. Instead, in real life you specify how much of the data you want to capture, and you keep computing singular vectors until you’ve passed the threshold. Alternatively, you specify the amount of computing resources you’d like to spend by fixing the number of singular vectors you’ll compute ahead of time, and settle for however good the $ k$-dimensional approximation is.

Before we get into any code or solve the 1-dimensional optimization problem, let’s prove the SVD theorem.

Proof of SVD theorem.

Recall we’re trying to prove that the first $ k$ singular vectors provide a linear subspace $ W$ which maximizes the squared-sum of the projections of the data onto $ W$. For $ k=1$ this is trivial, because we defined $ v_1$ to be the solution to that optimization problem. The case of $ k=2$ contains all the important features of the general inductive step. Let $ W$ be any best-approximating 2-dimensional linear subspace for the rows of $ A$. We’ll show that the subspace spanned by the two singular vectors $ v_1, v_2$ is at least as good (and hence equally good).

Let $ w_1, w_2$ be any orthonormal basis for $ W$ and let $ |Aw_1|^2 + |Aw_2|^2$ be the quantity that we’re trying to maximize (and which $ W$ maximizes by assumption). Moreover, we can pick the basis vector $ w_2$ to be perpendicular to $ v_1$. To prove this we consider two cases: either $ v_1$ is already perpendicular to $ W$ in which case it’s trivial, or else $ v_1$ isn’t perpendicular to $ W$ and you can choose $ w_1$ to be $ \textup{proj}_W(v_1)$ and choose $ w_2$ to be any unit vector perpendicular to $ w_1$.

Now since $ v_1$ maximizes $ |Av|$, we have $ |Av_1|^2 \geq |Aw_1|^2$. Moreover, since $ w_2$ is perpendicular to $ v_1$, the way we chose $ v_2$ also makes $ |Av_2|^2 \geq |Aw_2|^2$. Hence the objective $ |Av_1|^2 + |Av_2|^2 \geq |Aw_1|^2 + |Aw_2|^2$, as desired.

For the general case of $ k$, the inductive hypothesis tells us that the first $ k$ terms of the objective for $ k+1$ singular vectors is maximized, and we just have to pick any vector $ w_{k+1}$ that is perpendicular to all $ v_1, v_2, \dots, v_k$, and the rest of the proof is just like the 2-dimensional case.

$$\square$$Now remember that in the last post we started with the definition of the SVD as a decomposition of a matrix $ A = U\Sigma V^T$? And then we said that this is a certain kind of change of basis? Well the singular vectors $ v_i$ together form the columns of the matrix $ V$ (the rows of $ V^T$), and the corresponding singular values $ \sigma_i(A)$ are the diagonal entries of $ \Sigma$. When $ A$ is understood we’ll abbreviate the singular value as $ \sigma_i$.

To reiterate with the thoughts from last post, the process of applying $ A$ is exactly recovered by the process of first projecting onto the (full-rank space of) singular vectors $ v_1, \dots, v_k$, scaling each coordinate of that projection according to the corresponding singular values, and then applying this $ U$ thing we haven’t talked about yet.

So let’s determine what $ U$ has to be. The way we picked $ v_i$ to make $ A$ diagonal gives us an immediate suggestion: use the $ Av_i$ as the columns of $ U$. Indeed, define $ u_i = Av_i$, the images of the singular vectors under $ A$. We can swiftly show the $ u_i$ form a basis of the image of $ A$. The reason is because if $ v = \sum_i c_i v_i$ (using all $ n$ of the singular vectors $ v_i$), then by linearity $ Av = \sum_{i} c_i Av_i = \sum_i c_i u_i$. It is also easy to see why the $ u_i$ are orthogonal (prove it as an exercise). Let’s further make sure the $ u_i$ are unit vectors and redefine them as $ u_i = \frac{1}{\sigma_i}Av_i$

If you put these thoughts together, you can say exactly what $ A$ does to any given vector $ x$. Since the $ v_i$ form an orthonormal basis, $ x = \sum_i (x \cdot v_i) v_i$, and then applying $ A$ gives

$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned}Ax &= A \left ( \sum_i (x \cdot v_i) v_i \right ) \\\ &= \sum_i (x \cdot v_i) A_i v_i \\\ &= \sum_i (x \cdot v_i) \sigma_i u_i \end{aligned}$$If you’ve been closely reading this blog in the last few months, you’ll recognize a very nice way to write the last line of the above equation. It’s an outer product. So depending on your favorite symbols, you’d write this as either $ A = \sum_{i} \sigma_i u_i \otimes v_i$ or $ A = \sum_i \sigma_i u_i v_i^T$. Or, if you like expressing things as matrix factorizations, as $ A = U\Sigma V^T$. All three are describing the same object.

Let’s move on to some code.

A black box example

Before we implement SVD from scratch (an urge that commands me from the depths of my soul!), let’s see a black-box example that uses existing tools. For this we’ll use the numpy library.

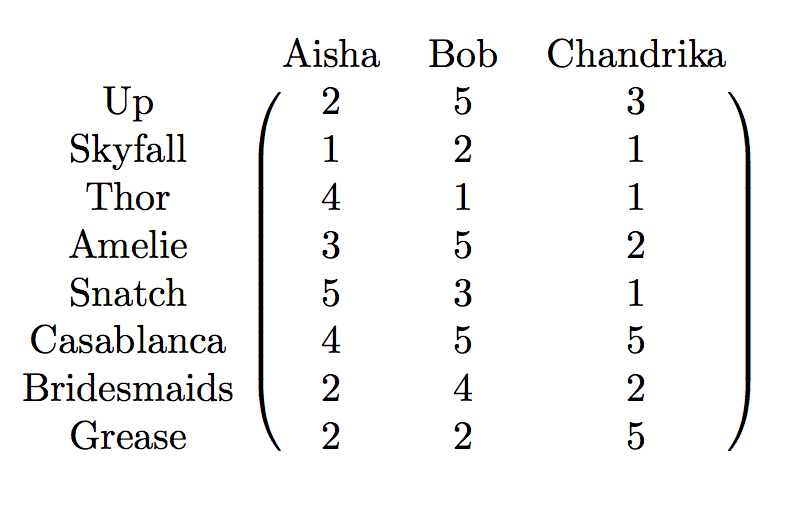

Recall our movie-rating matrix from the last post:

movieratings

The code to compute the svd of this matrix is as simple as it gets:

from numpy.linalg import svd

movieRatings = [

[2, 5, 3],

[1, 2, 1],

[4, 1, 1],

[3, 5, 2],

[5, 3, 1],

[4, 5, 5],

[2, 4, 2],

[2, 2, 5],

]

U, singularValues, V = svd(movieRatings)

Printing these values out gives

[[-0.39458526 0.23923575 -0.35445911 -0.38062172 -0.29836818 -0.49464816 -0.30703202 -0.29763321]

[-0.15830232 0.03054913 -0.15299759 -0.45334816 0.31122898 0.23892035 -0.37313346 0.67223457]

[-0.22155201 -0.52086121 0.39334917 -0.14974792 -0.65963979 0.00488292 -0.00783684 0.25934607]

[-0.39692635 -0.08649009 -0.41052882 0.74387448 -0.10629499 0.01372565 -0.17959298 0.26333462]

[-0.34630257 -0.64128825 0.07382859 -0.04494155 0.58000668 -0.25806239 0.00211823 -0.24154726]

[-0.53347449 0.19168874 0.19949342 -0.03942604 0.00424495 0.68715732 -0.06957561 -0.40033035]

[-0.31660464 0.06109826 -0.30599517 -0.19611823 -0.01334272 0.01446975 0.85185852 0.19463493]

[-0.32840223 0.45970413 0.62354764 0.1783041 0.17631186 -0.39879476 0.06065902 0.25771578]]

[ 15.09626916 4.30056855 3.40701739]

[[-0.54184808 -0.67070995 -0.50650649]

[-0.75152295 0.11680911 0.64928336]

[ 0.37631623 -0.73246419 0.56734672]]

Now this is a bit weird, because the matrices $ U, V$ are the wrong shape! Remember, there are only supposed to be three vectors since the input matrix has rank three. So what gives? This is a distinction that goes by the name “full” versus “reduced” SVD. The idea goes back to our original statement that $ U \Sigma V^T$ is a decomposition with $ U, V^T$ both orthogonal and square matrices. But in the derivation we did in the last section, the $ U$ and $ V$ were not square. The singular vectors $ v_i$ could potentially stop before even becoming full rank.

In order to get to square matrices, what people sometimes do is take the two bases $ v_1, \dots, v_k$ and $ u_1, \dots, u_k$ and arbitrarily choose ways to complete them to a full orthonormal basis of their respective vector spaces. In other words, they just make the matrix square by filling it with data for no reason other than that it’s sometimes nice to have a complete basis. We don’t care about this. To be honest, I think the only place this comes in useful is in the desire to be particularly tidy in a mathematical formulation of something.

We can still work with it programmatically. By fudging around a bit with numpy’s shapes to get a diagonal matrix, we can reconstruct the input rating matrix from the factors.

Sigma = np.vstack([

np.diag(singularValues),

np.zeros((5, 3)),

])

print(np.round(movieRatings - np.dot(U, np.dot(Sigma, V)), decimals=10))

And the output is, as one expects, a matrix of all zeros. Meaning that we decomposed the movie rating matrix, and built it back up from the factors.

We can actually get the SVD as we defined it (with rectangular matrices) by passing a special flag to numpy’s svd.

U, singularValues, V = svd(movieRatings, full_matrices=False)

print(U)

print(singularValues)

print(V)

Sigma = np.diag(singularValues)

print(np.round(movieRatings - np.dot(U, np.dot(Sigma, V)), decimals=10))

And the result

[[-0.39458526 0.23923575 -0.35445911]

[-0.15830232 0.03054913 -0.15299759]

[-0.22155201 -0.52086121 0.39334917]

[-0.39692635 -0.08649009 -0.41052882]

[-0.34630257 -0.64128825 0.07382859]

[-0.53347449 0.19168874 0.19949342]

[-0.31660464 0.06109826 -0.30599517]

[-0.32840223 0.45970413 0.62354764]]

[ 15.09626916 4.30056855 3.40701739]

[[-0.54184808 -0.67070995 -0.50650649]

[-0.75152295 0.11680911 0.64928336]

[ 0.37631623 -0.73246419 0.56734672]]

[[-0. -0. -0.]

[-0. -0. 0.]

[ 0. -0. 0.]

[-0. -0. -0.]

[-0. -0. -0.]

[-0. -0. -0.]

[-0. -0. -0.]

[ 0. -0. -0.]]

This makes the reconstruction less messy, since we can just multiply everything without having to add extra rows of zeros to $ \Sigma$.

What do the singular vectors and values tell us about the movie rating matrix? (Besides nothing, since it’s a contrived example) You’ll notice that the first singular vector $ \sigma_1 > 15$ while the other two singular values are around $ 4$. This tells us that the first singular vector covers a large part of the structure of the matrix. I.e., a rank-1 matrix would be a pretty good approximation to the whole thing. As an exercise to the reader, write a program that evaluates this claim (how good is “good”?).

The greedy optimization routine

Now we’re going to write SVD from scratch. We’ll first implement the greedy algorithm for the 1-d optimization problem, and then we’ll perform the inductive step to get a full algorithm. Then we’ll run it on the CNN data set.

The method we’ll use to solve the 1-dimensional problem isn’t necessarily industry strength (see this document for a hint of what industry strength looks like), but it is simple conceptually. It’s called the power method. Now that we have our decomposition of theorem, understanding how the power method works is quite easy.

Let’s work in the language of a matrix decomposition $ A = U \Sigma V^T$, more for practice with that language than anything else (using outer products would give us the same result with slightly different computations). Then let’s observe $ A^T A$, wherein we’ll use the fact that $ U$ is orthonormal and so $ U^TU$ is the identity matrix:

$$\displaystyle A^TA = (U \Sigma V^T)^T(U \Sigma V^T) = V \Sigma U^TU \Sigma V^T = V \Sigma^2 V^T$$So we can completely eliminate $ U$ from the discussion, and look at just $ V \Sigma^2 V^T$. And what’s nice about this matrix is that we can compute its eigenvectors, and eigenvectors turn out to be exactly the singular vectors. The corresponding eigenvalues are the squared singular values. This should be clear from the above derivation. If you apply $ (V \Sigma^2 V^T)$ to any $ v_i$, the only parts of the product that aren’t zero are the ones involving $ v_i$ with itself, and the scalar $ \sigma_i^2$ factors in smoothly. It’s dead simple to check.

Theorem: Let $ x$ be a random unit vector and let $ B = A^TA = V \Sigma^2 V^T$. Then with high probability, $ \lim_{s \to \infty} B^s x$ is in the span of the first singular vector $ v_1$. If we normalize $ B^s x$ to a unit vector at each $ s$, then furthermore the limit is $ v_1$.

Proof. Start with a random unit vector $ x$, and write it in terms of the singular vectors $ x = \sum_i c_i v_i$. That means $ Bx = \sum_i c_i \sigma_i^2 v_i$. If you recursively apply this logic, you get $ B^s x = \sum_i c_i \sigma_i^{2s} v_i$. In particular, the dot product of $ (B^s x)$ with any $ v_j$ is $ c_i \sigma_j^{2s}$.

What this means is that so long as the first singular value $ \sigma_1$ is sufficiently larger than the second one $ \sigma_2$, and in turn all the other singular values, the part of $ B^s x$ corresponding to $ v_1$ will be much larger than the rest. Recall that if you expand a vector in terms of an orthonormal basis, in this case $ B^s x$ expanded in the $ v_i$, the coefficient of $ B^s x$ on $ v_j$ is exactly the dot product. So to say that $ B^sx$ converges to being in the span of $ v_1$ is the same as saying that the ratio of these coefficients, $ |(B^s x \cdot v_1)| / |(B^s x \cdot v_j)| \to \infty$ for any $ j$. In other words, the coefficient corresponding to the first singular vector dominates all of the others. And so if we normalize, the coefficient of $ B^s x$ corresponding to $ v_1$ tends to 1, while the rest tend to zero.

Indeed, this ratio is just $ (\sigma_1 / \sigma_j)^{2s}$ and the base of this exponential is bigger than 1.

$$\square$$If you want to be a little more precise and find bounds on the number of iterations required to converge, you can. The worry is that your random starting vector is “too close” to one of the smaller singular vectors $ v_j$, so that if the ratio of $ \sigma_1 / \sigma_j$ is small, then the “pull” of $ v_1$ won’t outweigh the pull of $ v_j$ fast enough. Choosing a random unit vector allows you to ensure with high probability that this doesn’t happen. And conditioned on it not happening (or measuring “how far the event is from happening” precisely), you can compute a precise number of iterations required to converge. The last two pages of these lecture notes have all the details.

We won’t compute a precise number of iterations. Instead we’ll just compute until the angle between $ B^{s+1}x$ and $ B^s x$ is very small. Here’s the algorithm

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import norm

from random import normalvariate

from math import sqrt

def randomUnitVector(n):

unnormalized = [normalvariate(0, 1) for _ in range(n)]

theNorm = sqrt(sum(x * x for x in unnormalized))

return [x / theNorm for x in unnormalized]

def svd_1d(A, epsilon=1e-10):

''' The one-dimensional SVD '''

n, m = A.shape

x = randomUnitVector(m)

lastV = None

currentV = x

B = np.dot(A.T, A)

iterations = 0

while True:

iterations += 1

lastV = currentV

currentV = np.dot(B, lastV)

currentV = currentV / norm(currentV)

if abs(np.dot(currentV, lastV)) > 1 - epsilon:

print("converged in {} iterations!".format(iterations))

return currentV

We start with a random unit vector $ x$, and then loop computing $ x_{t+1} = Bx_t$, renormalizing at each step. The condition for stopping is that the magnitude of the dot product between $ x_t$ and $ x_{t+1}$ (since they’re unit vectors, this is the cosine of the angle between them) is very close to 1.

And using it on our movie ratings example:

if __name__ == "__main__":

movieRatings = np.array([

[2, 5, 3],

[1, 2, 1],

[4, 1, 1],

[3, 5, 2],

[5, 3, 1],

[4, 5, 5],

[2, 4, 2],

[2, 2, 5],

], dtype='float64')

print(svd_1d(movieRatings))

With the result

converged in 6 iterations!

[-0.54184805 -0.67070993 -0.50650655]

Note that the sign of the vector may be different from numpy’s output because we start with a random vector to begin with.

The recursive step, getting from $ v_1$ to the entire SVD, is equally straightforward. Say you start with the matrix $ A$ and you compute $ v_1$. You can use $ v_1$ to compute $ u_1$ and $ \sigma_1(A)$. Then you want to ensure you’re ignoring all vectors in the span of $ v_1$ for your next greedy optimization, and to do this you can simply subtract the rank 1 component of $ A$ corresponding to $ v_1$. I.e., set $ A’ = A – \sigma_1(A) u_1 v_1^T$. Then it’s easy to see that $ \sigma_1(A’) = \sigma_2(A)$ and basically all the singular vectors shift indices by 1 when going from $ A$ to $ A’$. Then you repeat.

If that’s not clear enough, here’s the code.

def svd(A, epsilon=1e-10):

n, m = A.shape

svdSoFar = []

for i in range(m):

matrixFor1D = A.copy()

for singularValue, u, v in svdSoFar[:i]:

matrixFor1D -= singularValue * np.outer(u, v)

v = svd_1d(matrixFor1D, epsilon=epsilon) # next singular vector

u_unnormalized = np.dot(A, v)

sigma = norm(u_unnormalized) # next singular value

u = u_unnormalized / sigma

svdSoFar.append((sigma, u, v))

# transform it into matrices of the right shape

singularValues, us, vs = [np.array(x) for x in zip(*svdSoFar)]

return singularValues, us.T, vs

And we can run this on our movie rating matrix to get the following

>>> theSVD = svd(movieRatings)

>>> theSVD[0]

array([ 15.09626916, 4.30056855, 3.40701739])

>>> theSVD[1]

array([[ 0.39458528, -0.23923093, 0.35446407],

[ 0.15830233, -0.03054705, 0.15299815],

[ 0.221552 , 0.52085578, -0.39336072],

[ 0.39692636, 0.08649568, 0.41052666],

[ 0.34630257, 0.64128719, -0.07384286],

[ 0.53347448, -0.19169154, -0.19948959],

[ 0.31660465, -0.0610941 , 0.30599629],

[ 0.32840221, -0.45971273, -0.62353781]])

>>> theSVD[2]

array([[ 0.54184805, 0.67071006, 0.50650638],

[ 0.75151641, -0.11679644, -0.64929321],

[-0.37632934, 0.73246611, -0.56733554]])

Checking this against our numpy output shows it’s within a reasonable level of precision (considering the power method took on the order of ten iterations!)

>>> np.round(np.abs(npSVD[0]) - np.abs(theSVD[1]), decimals=5)

array([[ -0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00],

[ 0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00],

[ 0.00000000e+00, -1.00000000e-05, 1.00000000e-05],

[ 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00],

[ 0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00, 1.00000000e-05],

[ -0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00],

[ 0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00],

[ -0.00000000e+00, 1.00000000e-05, -1.00000000e-05]])

>>> np.round(np.abs(npSVD[2]) - np.abs(theSVD[2]), decimals=5)

array([[ 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, -0.00000000e+00],

[ -1.00000000e-05, -1.00000000e-05, 1.00000000e-05],

[ 1.00000000e-05, 0.00000000e+00, -1.00000000e-05]])

>>> np.round(np.abs(npSVD[1]) - np.abs(theSVD[0]), decimals=5)

array([ 0., 0., -0.])

So there we have it. We added an extra little bit to the svd function, an argument $ k$ which stops computing the svd after it reaches rank $ k$.

CNN stories

One interesting use of the SVD is in topic modeling. Topic modeling is the process of taking a bunch of documents (news stories, or emails, or movie scripts, whatever) and grouping them by topic, where the algorithm gets to choose what counts as a “topic.” Topic modeling is just the name that natural language processing folks use instead of clustering.

The SVD can help one model topics as follows. First you construct a matrix $ A$ called a document-term matrix whose rows correspond to words in some fixed dictionary and whose columns correspond to documents. The $ (i,j)$ entry of $ A$ contains the number of times word $ i$ shows up in document $ j$. Or, more precisely, some quantity derived from that count, like a normalized count. See this table on wikipedia for a list of options related to that. We’ll just pick one arbitrarily for use in this post.

The point isn’t how we normalize the data, but what the SVD of $ A = U \Sigma V^T$ means in this context. Recall that the domain of $ A$, as a linear map, is a vector space whose dimension is the number of stories. We think of the vectors in this space as documents, or rather as an “embedding” of the abstract concept of a document using the counts of how often each word shows up in a document as a proxy for the semantic meaning of the document. Likewise, the codomain is the space of all words, and each word is embedded by which documents it occurs in. If we compare this to the movie rating example, it’s the same thing: a movie is the vector of ratings it receives from people, and a person is the vector of ratings of various movies.

Say you take a rank 3 approximation to $ A$. Then you get three singular vectors $ v_1, v_2, v_3$ which form a basis for a subspace of words, i.e., the “idealized” words. These idealized words are your topics, and you can compute where a “new word” falls by looking at which documents it appears in (writing it as a vector in the domain) and saying its “topic” is the closest of the $ v_1, v_2, v_3$. The same process applies to new documents. You can use this to cluster existing documents as well.

The dataset we’ll use for this post is a relatively small corpus of a thousand CNN stories picked from 2012. Here’s an excerpt from one of them

$ cat data/cnn-stories/story479.txt

3 things to watch on Super Tuesday

Here are three things to watch for: Romney's big day. He's been the off-and-on frontrunner throughout the race, but a big Super Tuesday could begin an end game toward a sometimes hesitant base coalescing behind former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney. Romney should win his home state of Massachusetts, neighboring Vermont and Virginia, ...

So let’s first build this document-term matrix, with the normalized values, and then we’ll compute it’s SVD and see what the topics look like.

Step 1 is cleaning the data. We used a bunch of routines from the nltk library that boils down to this loop:

for filename, documentText in documentDict.items():

tokens = tokenize(documentText)

tagged_tokens = pos_tag(tokens)

wnl = WordNetLemmatizer()

stemmedTokens = [wnl.lemmatize(word, wordnetPos(tag)).lower()

for word, tag in tagged_tokens]

This turns the Super Tuesday story into a list of words (with repetition):

["thing", "watch", "three", "thing", "watch", "big", ... ]

If you’ll notice the name Romney doesn’t show up in the list of words. I’m only keeping the words that show up in the top 100,000 most common English words, and then lemmatizing all of the words to their roots. It’s not a perfect data cleaning job, but it’s simple and good enough for our purposes.

Now we can create the document term matrix.

def makeDocumentTermMatrix(data):

words = allWords(data) # get the set of all unique words

wordToIndex = dict((word, i) for i, word in enumerate(words))

indexToWord = dict(enumerate(words))

indexToDocument = dict(enumerate(data))

matrix = np.zeros((len(words), len(data)))

for docID, document in enumerate(data):

docWords = Counter(document['words'])

for word, count in docWords.items():

matrix[wordToIndex[word], docID] = count

return matrix, (indexToWord, indexToDocument)

This creates a matrix with the raw integer counts. But what we need is a normalized count. The idea is that a common word like “thing” shows up disproportionately more often than “election,” and we don’t want raw magnitude of a word count to outweigh its semantic contribution to the classification. This is the applied math part of the algorithm design. So what we’ll do (and this technique together with SVD is called latent semantic indexing) is normalize each entry so that it measures both the frequency of a term in a document and the relative frequency of a term compared to the global frequency of that term. There are many ways to do this, and we’ll just pick one. See the github repository if you’re interested.

So now lets compute a rank 10 decomposition and see how to cluster the results.

data = load()

matrix, (indexToWord, indexToDocument) = makeDocumentTermMatrix(data)

matrix = normalize(matrix)

sigma, U, V = svd(matrix, k=10)

This uses our svd, not numpy’s. Though numpy’s routine is much faster, it’s fun to see things work with code written from scratch. The result is too large to display here, but I can report the singular values.

>>> sigma

array([ 42.85249098, 21.85641975, 19.15989197, 16.2403354 ,

15.40456779, 14.3172779 , 13.47860033, 13.23795002,

12.98866537, 12.51307445])

Now we take our original inputs and project them onto the subspace spanned by the singular vectors. This is the part that represents each word (resp., document) in terms of the idealized words (resp., documents), the singular vectors. Then we can apply a simple k-means clustering algorithm to the result, and observe the resulting clusters as documents.

projectedDocuments = np.dot(matrix.T, U)

projectedWords = np.dot(matrix, V.T)

documentCenters, documentClustering = cluster(projectedDocuments)

wordCenters, wordClustering = cluster(projectedWords)

wordClusters = [

[indexToWord[i] for (i, x) in enumerate(wordClustering) if x == j]

for j in range(len(set(wordClustering)))

]

documentClusters = [

[indexToDocument[i]['text']

for (i, x) in enumerate(documentClustering) if x == j]

for j in range(len(set(documentClustering)))

]

And now we can inspect individual clusters. Right off the bat we can tell the clusters aren’t quite right simply by looking at the sizes of each cluster.

>>> Counter(wordClustering)

Counter({1: 9689, 2: 1051, 8: 680, 5: 557, 3: 321, 7: 225, 4: 174, 6: 124, 9: 123})

>>> Counter(documentClustering)

Counter({7: 407, 6: 109, 0: 102, 5: 87, 9: 85, 2: 65, 8: 55, 4: 47, 3: 23, 1: 15})

What looks wrong to me is the size of the largest word cluster. If we could group words by topic, then this is saying there’s a topic with over nine thousand words associated with it! Inspecting it even closer, it includes words like “vegan,” “skunk,” and “pope.” On the other hand, some word clusters are spot on. Examine, for example, the fifth cluster which includes words very clearly associated with crime stories.

>>> wordClusters[4]

['account', 'accuse', 'act', 'affiliate', 'allegation', 'allege', 'altercation', 'anything', 'apartment', 'arrest', 'arrive', 'assault', 'attorney', 'authority', 'bag', 'black', 'blood', 'boy', 'brother', 'bullet', 'candy', 'car', 'carry', 'case', 'charge', 'chief', 'child', 'claim', 'client', 'commit', 'community', 'contact', 'convenience', 'court', 'crime', 'criminal', 'cry', 'dead', 'deadly', 'death', 'defense', 'department', 'describe', 'detail', 'determine', 'dispatcher', 'district', 'document', 'enforcement', 'evidence', 'extremely', 'family', 'father', 'fear', 'fiancee', 'file', 'five', 'foot', 'friend', 'front', 'gate', 'girl', 'girlfriend', 'grand', 'ground', 'guilty', 'gun', 'gunman', 'gunshot', 'hand', 'happen', 'harm', 'head', 'hear', 'heard', 'hoodie', 'hour', 'house', 'identify', 'immediately', 'incident', 'information', 'injury', 'investigate', 'investigation', 'investigator', 'involve', 'judge', 'jury', 'justice', 'kid', 'killing', 'lawyer', 'legal', 'letter', 'life', 'local', 'man', 'men', 'mile', 'morning', 'mother', 'murder', 'near', 'nearby', 'neighbor', 'newspaper', 'night', 'nothing', 'office', 'officer', 'online', 'outside', 'parent', 'person', 'phone', 'police', 'post', 'prison', 'profile', 'prosecute', 'prosecution', 'prosecutor', 'pull', 'racial', 'racist', 'release', 'responsible', 'return', 'review', 'role', 'saw', 'scene', 'school', 'scream', 'search', 'sentence', 'serve', 'several', 'shoot', 'shooter', 'shooting', 'shot', 'slur', 'someone', 'son', 'sound', 'spark', 'speak', 'staff', 'stand', 'store', 'story', 'student', 'surveillance', 'suspect', 'suspicious', 'tape', 'teacher', 'teen', 'teenager', 'told', 'tragedy', 'trial', 'vehicle', 'victim', 'video', 'walk', 'watch', 'wear', 'whether', 'white', 'witness', 'young']

As sad as it makes me to see that ‘black’ and ‘slur’ and ‘racial’ appear in this category, it’s a reminder that naively using the output of a machine learning algorithm can perpetuate racism.

Here’s another interesting cluster corresponding to economic words:

>>> wordClusters[6]

['agreement', 'aide', 'analyst', 'approval', 'approve', 'austerity', 'average', 'bailout', 'beneficiary', 'benefit', 'bill', 'billion', 'break', 'broadband', 'budget', 'class', 'combine', 'committee', 'compromise', 'conference', 'congressional', 'contribution', 'core', 'cost', 'currently', 'cut', 'deal', 'debt', 'defender', 'deficit', 'doc', 'drop', 'economic', 'economy', 'employee', 'employer', 'erode', 'eurozone', 'expire', 'extend', 'extension', 'fee', 'finance', 'fiscal', 'fix', 'fully', 'fund', 'funding', 'game', 'generally', 'gleefully', 'growth', 'hamper', 'highlight', 'hike', 'hire', 'holiday', 'increase', 'indifferent', 'insistence', 'insurance', 'job', 'juncture', 'latter', 'legislation', 'loser', 'low', 'lower', 'majority', 'maximum', 'measure', 'middle', 'negotiation', 'offset', 'oppose', 'package', 'pass', 'patient', 'pay', 'payment', 'payroll', 'pension', 'plight', 'portray', 'priority', 'proposal', 'provision', 'rate', 'recession', 'recovery', 'reduce', 'reduction', 'reluctance', 'repercussion', 'rest', 'revenue', 'rich', 'roughly', 'sale', 'saving', 'scientist', 'separate', 'sharp', 'showdown', 'sign', 'specialist', 'spectrum', 'spending', 'strength', 'tax', 'tea', 'tentative', 'term', 'test', 'top', 'trillion', 'turnaround', 'unemployed', 'unemployment', 'union', 'wage', 'welfare', 'worker', 'worth']

One can also inspect the stories, though the clusters are harder to print out here. Interestingly the first cluster of documents are stories exclusively about Trayvon Martin. The second cluster is mostly international military conflicts. The third cluster also appears to be about international conflict, but what distinguishes it from the first cluster is that every story in the second cluster discusses Syria.

>>> len([x for x in documentClusters[1] if 'Syria' in x]) / len(documentClusters[1])

0.05555555555555555

>>> len([x for x in documentClusters[2] if 'Syria' in x]) / len(documentClusters[2])

1.0

Anyway, you can explore the data more at your leisure (and tinker with the parameters to improve it!).

Issues with the power method

Though I mentioned that the power method isn’t an industry strength algorithm I didn’t say why. Let’s revisit that before we finish. The problem is that the convergence rate of even the 1-dimensional problem depends on the ratio of the first and second singular values, $ \sigma_1 / \sigma_2$. If that ratio is very close to 1, then the convergence will take a long time and need many many matrix-vector multiplications.

One way to alleviate that is to do the trick where, to compute a large power of a matrix, you iteratively square $ B$. But that requires computing a matrix square (instead of a bunch of matrix-vector products), and that requires a lot of time and memory if the matrix isn’t sparse. When the matrix is sparse, you can actually do the power method quite quickly, from what I’ve heard and read.

But nevertheless, the industry standard methods involve computing a particular matrix decomposition that is not only faster than the power method, but also numerically stable. That means that the algorithm’s runtime and accuracy doesn’t depend on slight changes in the entries of the input matrix. Indeed, you can have two matrices where $ \sigma_1 / \sigma_2$ is very close to 1, but changing a single entry will make that ratio much larger. The power method depends on this, so it’s not numerically stable. But the industry standard technique is not. This technique involves something called Householder reflections. So while the power method was great for a proof of concept, there’s much more work to do if you want true SVD power.

Until next time!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.