For fixed integers $ r > 0$, and odd $ g$, a Moore graph is an $ r$-regular graph of girth $ g$ which has the minimum number of vertices $ n$ among all such graphs with the same regularity and girth.

(Recall, A the girth of a graph is the length of its shortest cycle, and it’s regular if all its vertices have the same degree)

Problem (Hoffman-Singleton): Find a useful constraint on the relationship between $ n$ and $ r$ for Moore graphs of girth $ 5$ and degree $ r$.

Note: Excluding trivial Moore graphs with girth $ g=3$ and degree $ r=2$, there are only two known Moore graphs: (a) the Petersen graph and (b) this crazy graph:

The solution to the problem shows that there are only a few cases left to check.

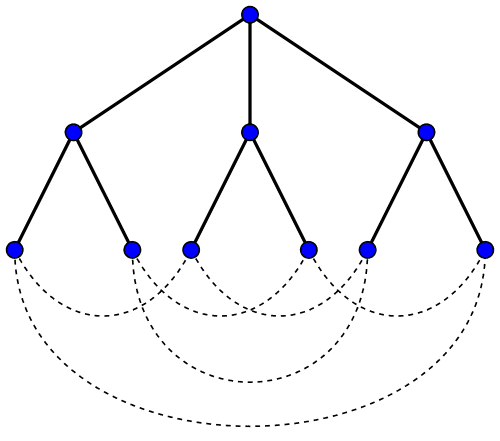

Solution: It is easy to show that the minimum number of vertices of a Moore graph of girth $ 5$ and degree $ r$ is $ 1 + r + r(r-1) = r^2 + 1$. Just consider the tree:

This is the tree example for $ r = 3$, but the argument should be clear for any $ r$ from the branching pattern of the tree: $ 1 + r + r(r-1)$

Provided $ n = r^2 + 1$, we will prove that $ r$ must be either $ 3, 7,$ or $ 57$. The technique will be to analyze the eigenvalues of a special matrix derived from the Moore graph.

Let $ A$ be the adjacency matrix of the supposed Moore graph with these properties. Let $ B = A^2 = (b_{i,j})$. Using the girth and regularity we know:

- $ b_{i,i} = r$ since each vertex has degree $ r$.

- $ b_{i,j} = 0$ if $ (i,j)$ is an edge of $ G$, since any walk of length 2 from $ i$ to $ j$ would be able to use such an edge and create a cycle of length 3 which is less than the girth.

- $ b_{i,j} = 1$ if $ (i,j)$ is not an edge, because (using the tree idea above), every two vertices non-adjacent vertices have a unique neighbor in common.

Let $ J_n$ be the $ n \times n$ matrix of all 1’s and $ I_n$ the identity matrix. Then

$$\displaystyle B = rI_n + J_n – I_n – A.$$We use this matrix equation to generate two equations whose solutions will restrict $ r$. Since $ A$ is a real symmetric matrix is has an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors $ v_1, \dots, v_n$ with eigenvalues $ \lambda_1 , \dots, \lambda_n$. Moreover, by regularity we know one of these vectors is the all 1’s vector, with eigenvalue $ r$. Call this $ v_1 = (1, \dots, 1), \lambda_1 = r$. By orthogonality of $ v_1$ with the other $ v_i$, we know that $ J_nv_i = 0$. We also know that, since $ A$ is an adjacency matrix with zeros on the diagonal, the trace of $ A$ is $ \sum_i \lambda_i = 0$.

Multiply the matrices in the equation above by any $ v_i$, $ i > 1$ to get

$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned}A^2v_i &= rv_i – v_i – Av_i \\\ \lambda_i^2v_i &= rv_i – v_i – \lambda_i v_i \end{aligned}$$Rearranging and factoring out $ v_i$ gives $ \lambda_i^2 – \lambda_i – (r+1) = 0$. Let $ z = 4r – 3$, then the non-$ r$ eigenvalues must be one of the two roots: $ \mu_1 = (-1 + \sqrt{z}) / 2$ or $ \mu_2 = (-1 – \sqrt{z})/2$.

Say that $ \mu_1$ occurs $ a$ times and $ \mu_2$ occurs $ b$ times, then $ n = a + b + 1$. So we have the following equations.

$$\displaystyle \begin{aligned} a + b + 1 &= n \\\ r + a \mu_1 + b\mu_2 &= 0 \end{aligned}$$From this equation you can easily derive that $ \sqrt{z}$ is an integer, and as a consequence $ r = (m^2 + 3) / 4$ for some integer $ m$. With a tiny bit of extra algebra, this gives

$$\displaystyle m(m^3 – 2m – 16(a-b)) = 15$$Implying that $ m$ divides $ 15$, meaning $ m \in \{ 1, 3, 5, 15\}$, and as a consequence $ r \in \{ 1, 3, 7, 57\}$.

$$\square$$Discussion: This is a strikingly clever use of spectral graph theory to answer a question about combinatorics. Spectral graph theory is precisely that, the study of what linear algebra can tell us about graphs. For an deeper dive into spectral graph theory, see the guest post I wrote on With High Probability.

If you allow for even girth, there are a few extra (infinite families of) Moore graphs, see Wikipedia for a list.

With additional techniques, one can also disprove the existence of any Moore graphs that are not among the known ones, with the exception of a possible Moore graph of girth $ 5$ and degree $ 57$ on $ n = 3250$ vertices. It is unknown whether such a graph exists, but if it does, it is known that

- The graph is not vertex-transitive

- Its automorphism group has size at most 375

You should go out and find it or prove it doesn’t exist.

Hungry for more applications of linear algebra to combinatorics and computer science? The book Thirty-Three Miniatures is a fantastically entertaining book of linear algebra gems (it’s where I found the proof in this post). The exposition is lucid, and the chapters are short enough to read on my daily train commute.

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.