Mathematics students often hear about the classic “blue-eyed islanders” puzzle early in their career. If you haven’t seen it, read Terry Tao’s excellent writeup linked above. The solution uses induction and the idea of *common knowledge—*I know X, and you know that I know X, and I know that you know that I know X, and so on—to make a striking inference from a seemingly useless piece of information.

Recreational mathematics is also full of puzzles involving prisoners wearing colored hats, where they can see others hats but not their own, and their goal is to each determine (often with high probability) the color of their own hat. Sometimes they are given the opportunity to convey a limited amount of information.

Over the last eight years I’ve been delighted by the renaissance of independent tabletop board and card games. Games leaning mathematical, like Set, have had a special place in my heart. Sadly, many games of incomplete information often fall to an onslaught of logic. One example is the popular game The Resistance (a.k.a. Avalon), in which players with unknown allegiances must either deduce which players are spies, or remain hidden as a spy while foiling a joint goal. With enough mathematicians playing, it can be easy to dictate a foolproof strategy. If we follow these steps, we can be 100% sure of victory against the spies, so anyone who disagrees with this plan or deviates from it is guaranteed to be a spy. Though we’re clearly digging a grave for our fun, it’s hard to close pandora’s logic box after it’s open. So I’m always on the lookout for games that resist being trivialized.

Enter Hanabi.

hanabi

A friend recently introduced me to the game, which channels the soul and complexion of the blue-eyed islanders and hat-donning prisoners into a delightful card game.

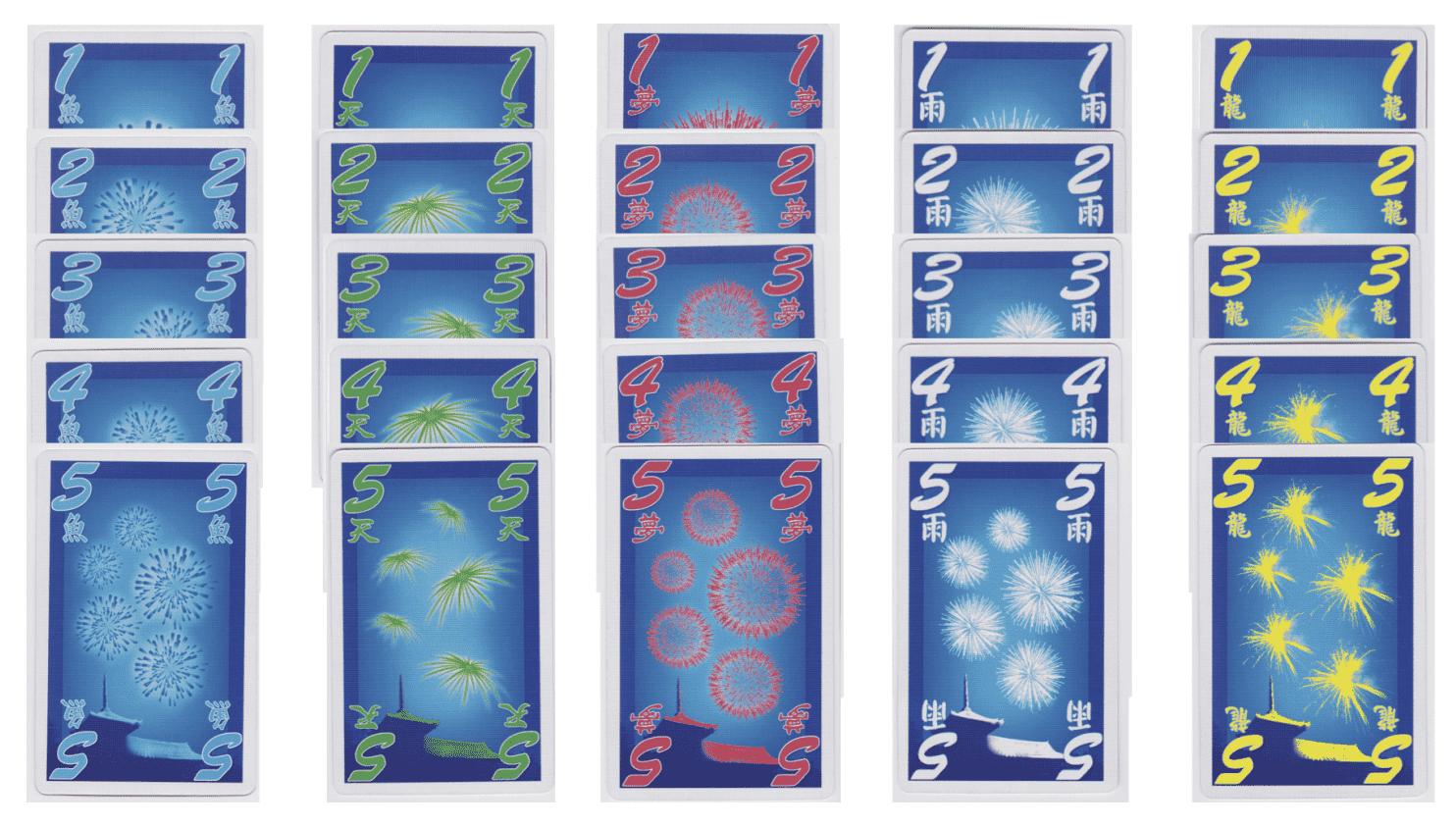

The game has simple rules: each player gets a hand that they may not see, but they reveal to all other players. The hands come from the following set of cards (with more 1’s than 2’s, and the fewest 5’s), and players work together, aiming to place cards from 1-5 in order in each color. It’s like solitaire, where stacks of different colors may progress independently, but a 2 must be placed before a 3.

Then the players take turns, and on each turn a player may do one of the following:

- Choose a card from your hand to play. If the chosen card cannot be played (e.g, it’s a red 3 but only a red 1 is on the table), everyone gets a strike. Three strikes ends the game in a loss.

- Use an information token (limited in supply) to give one piece of information to one other player; the allowed types of information are explained below.

- Choose a card from your hand to discard, and regain an information token for future use.

The information you can give to a player to choosing a single feature (a specific rank or color), and pointing to all cards in that player’s hand that have that feature. Example: “these two cards are green”, or “this card is a 4”. House rules dictate whether “no cards are blue” is a valid piece of information. Officially—I like to think it’s in the spirit of the blue-eyed islander’s puzzle where “someone has blue eyes”—you must be able to point at something to reveal information about it.

So the game involves some randomness (the draw), and some resource management (the information tokens), but the heart of the game is figuring out how to convey as much information as possible in a single clue.

Just like the blue-eyed islander’s puzzle, giving a public piece of information to one player can indicate much more. Imagine their are 4 players. I can see your hand, but if, after looking at your hand, I decide instead to give Blair a clue, that gives you information that what’s in Blair’s hand is more valuable for me to reveal to her than what’s in your hand would be to reveal to you.

Another trick: say I know I have a 4, and say it’s the beginning of the game where 4’s are not playable, and the board has a blue 1 on it. If you play before me and you tell me that that same 4 and a second card are both blue, what does that tell me? It was certainly somewhat redundant: you told me more information about a card I knew was not playable, and seemingly not super-helpful information about a second card. After some reflection you can often infer that not only is the second card a blue 2, but also that you have at least one more 2 elsewhere in your hand that’s not immediately playable. That’s a lot of information!

The idea of common knowledge takes it down a rabbit hole that I haven’t quite gotten my head around, but which makes the game continually fun. If I know that you know that I can infer the above scenario with the blue 2, then you not giving me that clue tells me that either that situation isn’t present in my hand, or else that whatever information you’re instead giving to Matthieu is a higher priority. The more the group can understand to be commonly inferable (say, discussing strategies before starting the game), the more one can take advantage of common knowledge. The game starts to feel like a logical olympiad, where your worst enemy is your fallible memory, and if people aren’t playing at the same level, relying too much on an inference your teammate didn’t intend can cause grave mistakes!

It’s a guaranteed hit at your next gathering of logic-loving mathemalites!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.