Two men start running at each other with loaded pistols, ready to shoot!

It’s a foggy morning for a duel. Newton and Leibniz have decided this macabre contest is the only way to settle their dispute over who invented Calculus. Each pistol is fitted with a silencer and has a single bullet. Neither can tell when the other has attempted a shot, unless, of course, they are hit.

Newton and Leibniz both know that the closer they get to their target, the higher the chance of a successful shot. Eventually they’ll be standing nose-to-nose: a guaranteed hit! But the longer each waits, the more opportunity they give their opponent to fire. If they both fire and miss, mild embarrassment ensues and they resolve to try again tomorrow. When should they shoot to maximize their chance at victory?

This is the so-called silent duel problem, and as you might have guessed it can be phrased without any violence.

Two players compete to succeed in taking some action in the interval $ [0,1]$. They are given a function $ P(t)$ that describes the probability of success if the action is taken at time $ t$. Since the two men are “running” at each other, $ P(t)$ is assumed to be increasing, with $ P(0) = 0, P(1) = 1$. If Player 1 succeeds in their action first, Player 1 gets a dollar (1 unit of utility) from Player 2; if Player 2 succeeds, Player 1 loses a dollar to Player 2. What strategy should they use to maximize their expected payoff?

Yet another phrasing of the problem is that a beautiful young woman is arriving at a train station, and two suitors are competing to pick her up. If she arrives and nobody is there to pick her up, she waits for the first suitor to arrive. If a suitor arrives and the woman is not there, the suitor assumes she has already been picked up and leaves. I like the duel version better, because what self-respecting woman can’t arrange her own ride these days? Either way, neither example has aged well. We should come up with a modern version where people are racing to McDonald’s to get Mulan Szechuan Sauce.

I originally heard about this problem in a game theory course I took in undergrad, coincidentally the same class where I met my wife. See section 3 of the course notes by Anthony Mendes, which neatly describes how to solve the silent duel when $ P(x) = x$. I remember spending a lot of time confused about this problem, and wrote out my solution over and over again until I felt I understood it.

Almost ten years later, I found a renewed interest in the silent duel when a colleague posed the following variant (having no leads on how to solve it). A government agency releases daily financial data concerning the market every morning at 6AM, and gives API access to it. In this version I’ll say that this data describes the demand for wheat and sheep. If you can get this data before anyone else, even an extra few milliseconds gives you an edge in the market for that day. You can buy up all the wheat if there’s a shortage, or short sheep futures if there’s a surplus.

There are two caveats. First caveat: 6AM is not precise because your clock deviates from the data provider’s clock. Maybe there’s a person who has to hit a button, and they took an extra few seconds to take a bite of their morning donut. If you call the API too early, it will respond, “Please try again later.” If you call the API after the data has been released, you receive the data immediately. Second caveat: since everyone is racing to get this data first, the API rate limits you to 6 requests per minute. If you go over, your account is blocked for 12 hours and you can’t get the data at all that day. You need a Scrooge-McDuckian vault of money to afford a new account, so you’re stuck with the one.

Assuming you have enough time to watch when the data gets released, you can construct a cumulative distribution $ P(t)$, which for a time $ t$ describes the probability that the data has been released before time $ t$. I.e., the probability of success if you call the API at time $ t$. If we assume the distribution falls within a single minute around 6AM, then we see a strikingly similarity between this problem and a silent duel with six shots. Perhaps it’s not exactly the same, since there are many more than two players in the game, but it’s close. Perhaps you can assume two players, but you (Player 1) get six shots and your opponent (Player 2) gets some larger number.

I was downright twitterpated to see a natural problem fit so neatly and unexpectedly into a bit of math I remembered, but hadn’t thought about for a decade. The solution was too detailed for me to remember it on the spot (I recall it involved some integrals and curious discontinuities), so I told my colleague I’d go find the paper that solves this problem.

Thus began my journey down the rabbit hole. The first hurdle was that I didn’t know what to call the problem. I found my professor’s notes from the course, but they didn’t provide a definitive name beyond “interval games.” After combing through some textbooks and, more helpfully, crawling back along the graph of citations, I discovered the name *silent duel—*and noisy duel for the variant where the shooters can hear each other’s attempts. However, no textbook I looked at actually provided a full explanation or proof of the solution. They just said, “optimal strategies have been proven to exist,” or detailed a simplification involving one or two bullets. And after a few more hours of looking I found the title of the original paper that solved this problem in the generality I wanted.

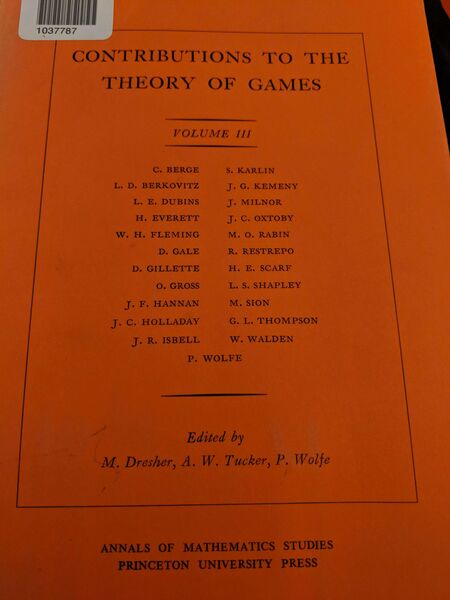

Rodrigo Restrepo. Tactical Problems Involving Several Actions. Contributions to the Theory of Games, Vol. III. 1957.

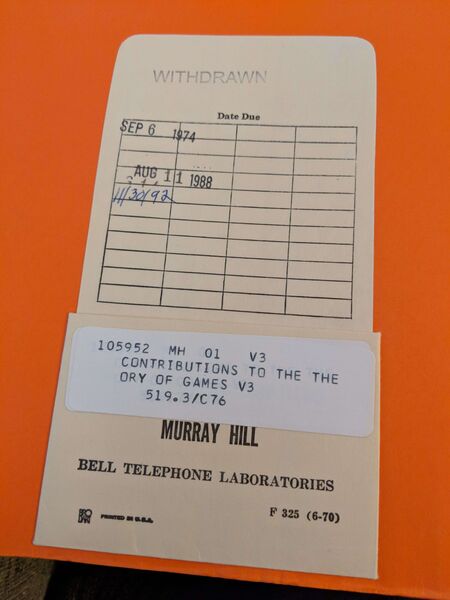

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find a digital copy. I did find a copy being sold on Amazon by a third-party seller. Apparently this seller bought old journal proceedings in bulk from the Bell Laboratories library after they closed down. I bought a copy, and according to the Amazon listing there are only 20-odd copies left.

I was also pleased to see the many recognizable names on the cover.

- Rabin: Turing Award winner who invented nondeterminism as a computing concept (among many other accomplishments)

- Gale & Shapley: inventors of the Stable Marriage algorithm, the latter of whom won the Nobel Price in Economics for subsequent work on applying it.

- Berge: one of the leaders who established graph theory and combinatorics as mathematical disciplines in their own right

- Karlin: a big name in math for social sciences (think of Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem).

- Milnor: Fields medalist and heavyweight in differential topology.

I thought about how many of these old papers might be lost to history with no digital record. It’s a shame, because the silent duel is a cool problem, absent from many books, and, prompted by my recent discussions, applicable to software! Rodrigo Restrepo in particular seems to have had no PhD students. He might be a faculty emeritus at the University of British Columbia (linke is now dead) studying mathematical biology, but I wasn’t able to locate a website (or even a photo!) to cross-check publications. If any UBC math faculty read this, perhaps they can provide more details about who Dr. Restrepo is.

All of this culminated in the inevitable next steps. Buy the manuscript, re-typeset the paper in TeX, grok the theorem and the construction, put the paper on arXiv to make it accessible for the foreseeable future, and then use my newfound knowledge to corner the market on sheep futures once and for all!

I drafted the TeX rewrite (still has a few typos), and started working through the paper. Then I realized I had committed to publishing my book by the end of 2018. I forced myself to put it aside, and now I’ve returned to study it. I’ll detail my exploration of the paper and the code to implement the solution in subsequent posts. I intend the subsequent posts to be as much of a narrative of my process working through a paper as it is about the math itself (to be honest, the paper could be clearer, but I chalk it up to pre-computer era descriptions of algorithms). In general, I’d like to explore more and different kinds of ways to share and explore math on the internet.

In the mean time, intrepid readers can venture forth to see the draft on Github.

Until next time!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.