Editor’s note: This essay was originally published in 2019. I have made minor edits in this republishing.

There was a MathOverflow thread about mathematically interesting games for 5–6 year olds. A lot of the discussion revolved around how young age 5 really is, and how we should temper expectations because we don’t really remember what it’s like to be 5. In response to an enormous answer by Alexander Chervov, user LSpice quipped, “‘Daddy, daddy, let’s play another in the infinite indexed family of perfect-information draw-free cheap-to-construct two-player games!’” That being said, Martín-Blas Pérez Pinilla’s “sprouts” game piqued my interest to find optimal strategies.

Most abstract logic games that are interesting to mathy folks are only interesting when you start asking questions beyond core gameplay. For example, the game Set is interesting when you ask, “how many cards can you have with no set?” or similar tricks to determine the last un-dealt card in a deck just by viewing the remaining board. These have little to do with skill at playing the game.

I’ve found that children under a certain age, maybe 7 or 8, haven’t learned how to be curious about such questions yet. They like knowing things and experiencing things. They enjoy surprising patterns or natural phenomena (like vinegar and baking soda), but still aren’t really curious enough about them to be persistent in studying them.

For children to exercise mathematical reasoning skills, and for teachers and parents to get the opportunity to teach curiousity and persistence, they have to be motivated. People with an eye for science, people who in their adulthood marvel at the splendor of nature, often neglect that at age 5, there is one simple thing that kids embrace with all their being, justification-free, which can be used as a vessel for abstract reasoning: storytelling. Be good at storytelling.

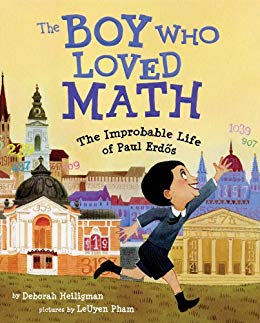

A few years ago, my cousin’s daughter was 5 years old. I’ll refer to her as Anna. Anna is of Hungarian descent, lives in Germany, and speaks functional English. My cousin knew her daughter was bright, but she was at a loss for what to give Anna to occupy her mind. So naturally I sent my cousin the book, “The Boy Who Loved Math.”

Cover of The Boy Who Loved Math

It’s a story about Paul Erdős, the famous Hungarian mathematician. The book is in English, about a Hungarian boy, and involves a strict German nanny. Naturally, Anna loved the book because she had someone to identify with her multiplex identity.

At its most mathematical, “The Boy Who Loved Math” explains what a prime number is, and Anna learned it immediately. My cousin told me about how one day they were listening to the radio in the car, and a game show was playing where the prize-winning question was (I paraphrase), “What is the name for a number that has only itself and 1 as a factor?” The contestant on the radio couldn’t answer, but Anna pipes up, “That’s easy, it’s a prime!” To the best of my knowledge, she had no interest in math before this, and she had no use for knowing what a prime number is. But simply having the idea of a prime number wrapped up in a story about someone like her was enough to pique her interest.

This story has nothing to do with math, but has a lot to do with storytelling.

I worked as a day camp counselor for a few summers in high school and college. My main age group was 5-6 year old boys and girls. It’s a lovely age group because they’re old enough to understand complex ideas, but too young to directly challenge you when you lie to them. And I lied like the wind.

My shtick was to tell the kids that the summer camp was a secret agent training camp. All the counselors were former secret agents that had retired and were now training the next generation. By the end of each 3-week session, most of the kids figured out that it was make-believe, but it was fun make-believe and there was just enough to keep it plausible.

The crown jewel of this act was that it was an infinite time sink. Often enough, our schedule had us playing an hour of field hockey followed by an hour of tennis in 95 degree heat (even in normal weather, a 6 year old won’t have more than 15 minutes of tennis in them before they get bored or frustrated by a lack of hand-eye coordination). On such hot days, I would end the activities early and have the kids gather around in the shade to regale them with a tale about a “mission” another counselor and I had embarked on in our long, storied career.

The formula was pretty simple:

- Pick an evil boss: Doctor Euler.

- Choose an exotic locale for a base: inside an iceberg.

- Pick an “element” (sand, grass, dirt, mud) for the evil boss’s henchmen to be built out of (so that we can “kill” them without resorting to gratuitous violence; guns don’t work on grass monsters).

As you can tell from the name of the evil boss, I liked to slip in math names for things. Turns out, mathematicians have terrifying and authentic names for evil geniuses: Doctor Euler, Doctor Tychonoff, Doctor Lagrange, Doctor Gauss. The headquarters of the evil Corporation was called the Vector Space. Our organization of secret agents was the Free Group. You get the idea.

The stories were almost entirely improv. I provided the setting and the names, and then threw in random obstacles: a fork in the road, an Indiana Jonesesque boulder rolling toward you, etc. Then I would pause the story, and ask the kids: what would you do in this situation?

To be clear: I had no idea where the story was going. But the kids took it so seriously, they would craft all kinds of ideas, and eventually I’d pick one and say, “that’s exactly what we did.” I get a free story idea, the kids get validation for thinking logically or creatively, and they become part of the story. They would even add unexpected details. When I introduced “Doctor Euler” (a German name pronounced “OY-lurr”) one kid squealed, “Ooooh! Is his hair all oily and green?!” Of course it was.

The second best part of the charade was that it incentivized participation in camp activities. For example, the camp rented a climbing wall that some of the kids were afraid to attempt. So the next day I had a tale about a mission to infiltrate Doctor Archimedes’s cliffside lair, and the only way in was to climb up from the bottom. The next time we did climbing, everyone gave it a shot.

How could I justify the drama activities to the campers? On one mission I had to infiltrate a party in which the top executives of the evil corporation were meeting. I had to act well to play my part and not raise suspicion. For sports, physical strength and agility. For arts and crafts, MacGyvering spy devices on the fly (plus making spy masks!).

If I had wanted to, I could have easily incorporated learning math as part of a plot line, and used it to reinforce the importance of math. When you’re invested in a story, learning and thinking are natural and easy.

Stories don’t just get people interested, they get them invested in their own abilities. They make them feel welcome. They can make a frustrating or uncomfortable event tolerable, or even good in retrospect.

I was a Boy Scout, and when I was 16 I was a senior patrol leader. This basically meant I ran the weekly meetings and helped organize outings. The youngest scouts in the troop were 10 years old, and many of them felt out of place as the youngest members. On certain long outings with no young scouts attending, they might get homesick or find difficulty making friends.

One strategy I employed to make them feel more welcome—emulating a scout who did this when I was younger—was to invent outlandish, Chuck Norrissian tales about their feats of bravery and strength on these outings. At the first weekly scout meeting after the outing, I’d close the meeting by relaying the tale to the troop (doubling as an advertisement for how fun the outings were), and bestowing a relevant nickname on the scout.

For example, on a snow camping trip one scout didn’t bring proper clothes, so his feet were soaked and he was cold and miserable. His fabricated story involved an epic snowball fight during which he single-handedly defeated all the dads and other scouts, kicking off his shoes and going barefoot because shoes slowed him down. By the end, his feet were literal blocks of ice, and so he went to stand on top of the fire to thaw them. He got the nickname Ice Pack, and the other scouts thought he was pretty cool.

It turns out, fear and pain can be amplified or diminished depending on the stories we tell. Some researchers in Chicago studied how parents fear of math can be endowed in the child when they say things like “I don’t like math,"—in fact, saying “it’s okay if you don’t like math because I don’t like it either” is even worse than completely ignoring it—but math anxieties can be counteracted by normalizing it in family life. The NPR article linked above downplays the technique, but in the study they had parents read bedtime stories involving math to their kids, and then ask the kids questions about the math in the stories.

With all the ways I have used storytelling in my life, it’s obvious that storytelling was crucial here. I doubt simply giving a kid exercises to do before bed would have worked. A story welcomes you to participate, to play out what would or could have happened in your mind. You think about a good story later, recounting its steps in your head and imagining yourself in the middle. That behavior is the first step toward mathematical inquiry, where a good problem nags at you to explore it further. The story helps you feel you belong, and if you belong around math, it won’t seem scary even when it’s hard.

In my view, storytelling is the key to any mathematical encounter. For kids, and for people for whom math is foreign and scary, the storytelling is never about the math. Rather, the math delightfully grows out of the story. Simple examples reign supreme, and you keep prompting the listener with, “look at this curious pattern,” and, “why does this always work?”

As you become more comfortable with math, the emphasis of a good story transitions to having the mathematical objects take center stage. They are the actors, their surprising behaviors drive the plot, and the theorems and proofs are the punchline, and the generalization of the proof technique is the epilogue cliffhanger.

What’s really needed is more story-focused content between basic number sense and undergraduate level math. YouTube channels like Numberphile (particularly Tadashi Tokieda’s episodes that explore curious toys) are a fantastic invitation. More could exist in various forms, particularly those that transition from these delightful introductions to deeper, more complete theories while still holding on to the stories. The closest I’ve found for young children is the comic book series Beast Academy.

To have good mathematical content revolving around stories, we should learn to tell stories well. I think this is difficult, but there’s demand for it when it’s done well.

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.

This article is syndicated on: